You may think eating fast just saves time, but it changes how your body processes food from the first chew to the last swallow. When you rush meals, you swallow larger pieces and extra air, blunt saliva’s enzymatic role, and shortcut the 20-minute brain–gut loop that tells you when to stop eating. This combination increases bloating, reflux, nutrient malabsorption, and the chance you’ll overeat before fullness signals reach your brain.

If you want to feel less bloated, reduce heartburn, and avoid sneaky calorie creep, this article explains the mechanisms behind those symptoms and what to watch for. Expect clear, practical steps you can test at your next meal and evidence-based explanations of why slowing down helps both short-term comfort and long-term metabolic risk.

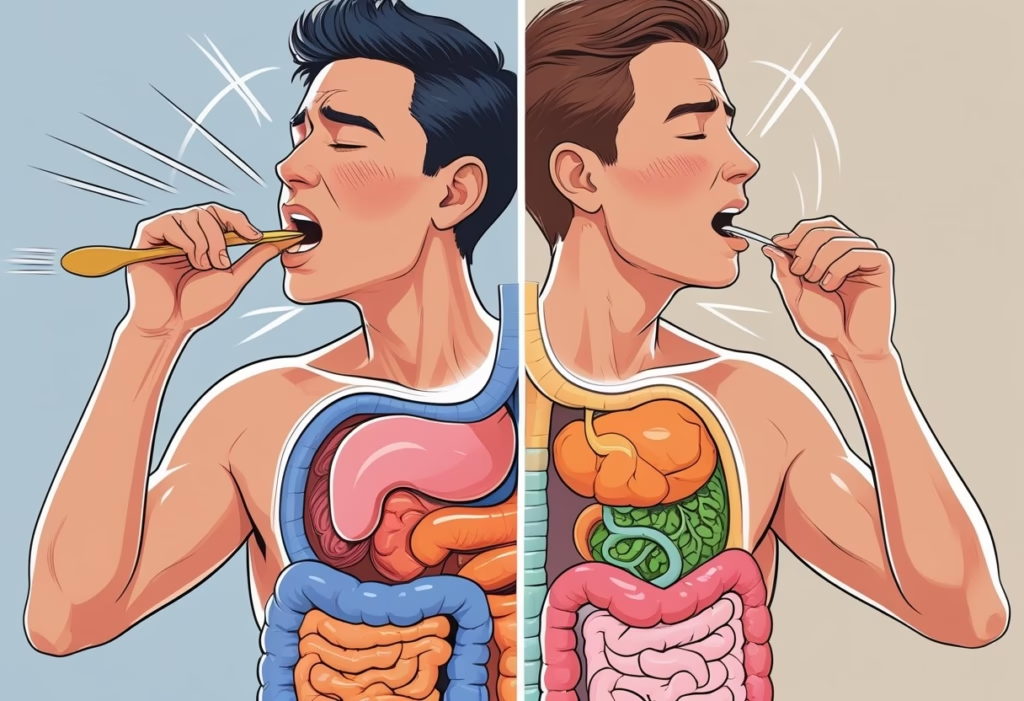

How Eating Too Fast Disrupts Digestion

Eating rapidly changes three linked parts of digestion: how food is prepared in your mouth, how nutrients become available, and how much air you swallow. Each of these alters signals and mechanics in ways that raise the chance of discomfort, excess gas, and poor nutrient use.

Digestion Starts in the Mouth

Your mouth begins chemical and mechanical digestion the moment food enters it. Saliva contains enzymes (amylase and lipase) that start breaking down carbohydrates and fats; if you rush, less saliva mixes with food, so those enzymes have less contact time and your stomach must compensate.

Chewing also triggers neural and hormonal signals that prime the stomach, pancreas, and gallbladder. When you eat too fast, your body gets fewer of those preparatory signals, so acid, bile, and pancreatic enzymes may not arrive in optimal timing or quantity. That mismatch increases the likelihood of indigestion and heartburn because the stomach works harder on larger, less‑prepared pieces.

Chewing and Nutrient Absorption

When you don’t chew thoroughly, larger food particles reach the stomach and small intestine. Larger particles reduce surface area for enzymes to act on, which slows digestion and can lower absorption of nutrients like starches, fats, and certain micronutrients bound in fibrous matrices.

Poorly chewed foods can sit longer in the stomach or pass to the intestine in more intact pieces, raising fermentation by gut bacteria. That process produces gas and can cause cramping or bloating. Studies link prolonged mastication with lower subsequent food intake and better satiety signaling, which shows chewing affects hormones that regulate hunger and fullness; eating fast disrupts that hormonal feedback loop.

Swallowing Air and Bloating

When you gulp, you swallow extra air (aerophagia). That air enters the stomach and intestines, increasing intra‑abdominal pressure and producing visible bloating or trapped gas. You may feel pressure, belching, or sharp pains that mimic worse conditions.

Air plus larger, under‑digested particles also feeds bacterial fermentation in the colon, increasing hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide production. That raises the chance of excess gas and discomfort. Slower bites, smaller mouthfuls, and conscious pauses reduce aerophagia and the downstream symptoms you actually feel after a meal.

Missed Fullness Signals and Overeating

Eating too fast short-circuits the body’s timing for recognizing fullness and makes it easier to consume more calories than you need. The next parts explain how delayed signaling, hormonal responses, and portion habits combine to drive overeating and weight gain.

Delayed Satiety Response

Your stomach needs time to stretch and send mechanical signals that you’re getting full. It typically takes about 15–30 minutes for stretch receptors and downstream neural pathways to register meal volume and communicate that information to your brain.

If you finish a meal in under 10–15 minutes, those signals often arrive after you’ve already consumed extra calories. That mismatch explains why you can feel uncomfortably full or still hungry shortly after a rushed meal. Repeatedly eating this way trains you to eat larger amounts before satiety kicks in, which raises daily calorie intake and increases the likelihood of weight gain over months to years.

Hunger and Fullness Hormones

Several hormones coordinate hunger and satiety; when you eat quickly, their timing gets disrupted. Ghrelin, which rises before meals, falls as you eat; leptin and incretins like GLP‑1 and CCK help signal fullness after food enters the gut.

Rapid ingestion accelerates glucose and nutrient delivery but doesn’t allow gut-derived hormones adequate time to rise in step with the calories eaten. The result: ghrelin may not drop quickly enough and GLP‑1/CCK responses lag, so your brain receives weaker fullness signals. Clinical studies link faster eating to blunted satiety hormone patterns and higher post-meal glucose spikes, both of which promote continued hunger and make portion restraint harder.

Portion Control Challenges

Rushed eating changes behavior and environment in ways that undermine portion control. When you eat quickly, you tend to take larger bites, swallow with less chewing, and ignore sensory cues like taste, texture, and gradual stomach stretch.

These habits make it easy to finish a plate before you notice fullness cues. Practical markers—such as stopping when your stomach feels comfortably settled or waiting 20 minutes before seconds—work because they align your behavior with physiological signal timing. Without those pauses, habitual fast eating normalizes oversized portions and increases the risk of habitual overeating and gradual weight gain.

Digestive Symptoms Caused by Fast Eating

Eating quickly commonly leads to specific digestive problems you can feel within minutes to hours: poor breakdown of food, excess swallowed air, and delayed fullness signaling. These mechanisms raise your risk for indigestion, heartburn, acid-related inflammation, and uncomfortable gas and bloating.

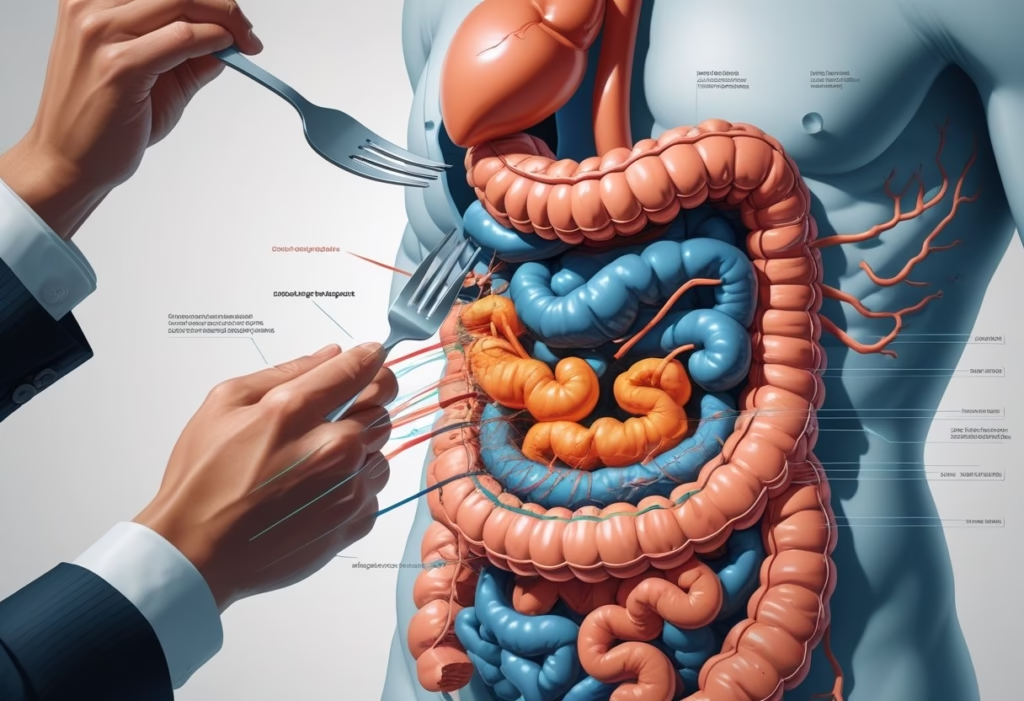

Indigestion and Heartburn

When you eat fast, you often take larger bites and don’t chew enough, so larger food particles reach the stomach. That forces your stomach to work harder and produce more acid and digestive enzymes to break food down, which increases the chance of indigestion — a persistent discomfort characterized by upper abdominal pain, nausea, or a burning sensation.

Swallowing extra air while you rush through a meal adds pressure in your stomach. That pressure can push acid upward, causing heartburn (a burning behind the breastbone). Studies link faster eating pace with more frequent post-meal fullness and heartburn episodes, and slower chewing increases hormone signals that tell you when to stop eating. Managing bite size and chewing more thoroughly reduces the mechanical and chemical triggers that produce indigestion and heartburn.

Acid Reflux and Gastritis

Eating rapidly increases the volume of food and acid the stomach must handle at once, which can overwhelm the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). If the LES relaxes or is pressured by a distended stomach, gastric contents can reflux into the esophagus, causing acid reflux symptoms like regurgitation and sore throat.

Repeated reflux and continual high-acid exposure can irritate the stomach lining and esophagus. That irritation may worsen or contribute to gastritis — inflammation of the stomach lining — which presents as burning pain, nausea, or a persistent uneasy feeling after meals. Clinical research associates fast eating with higher rates of reflux-related conditions and metabolic disturbances that can exacerbate mucosal inflammation. Slowing your pace reduces gastric distention and the mechanical factors that provoke LES dysfunction and mucosal irritation.

Gas and Bloating

Fast eating increases aerophagia — swallowing air — and limits chewing, so larger food particles reach the gut. Gut bacteria then ferment those larger particles more rapidly, producing excess gas that causes bloating, cramping, and flatulence.

You may also notice tightness or visible abdominal swelling after meals when you eat quickly. This stems from a combination of trapped gas and delayed gastric emptying due to insufficiently processed food. Evidence shows slower, more mindful eating reduces swallowed air and improves mechanical digestion, which in turn lowers excess gas production and the uncomfortable bloating that follows.

Long-Term Health Impacts of Eating Quickly

Eating too fast can change how much you eat, how your body handles glucose and insulin, and your long-term risk for chronic conditions. These effects build over months to years and are linked to measurable changes in appetite hormones, portion size, and metabolic markers.

Weight Gain and Obesity Risk

When you eat quickly, you often swallow larger bites and chew less, which reduces the mechanical breakdown of food and slows the signal cascade that tells your brain you’re full. Your stomach needs roughly 15–20 minutes to trigger fullness signals to the brain; finishing a meal before that window frequently leads to consuming extra calories in one sitting. Studies and meta-analyses link faster eating rates to higher body mass index and greater likelihood of overweight or obesity.

Fast eating also encourages larger habitual portion sizes. You’re more likely to snack sooner after a meal and to prefer energy-dense processed foods that are easy to eat quickly. Over months, those extra calories and more frequent eating episodes translate into sustained weight gain.

Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance

Eating rapidly contributes to patterns—overeating, post-meal blood sugar spikes, and visceral fat accumulation—that increase the odds of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome combines elevated waist circumference, high triglycerides, low HDL, hypertension, and impaired fasting glucose. Research shows fast eaters have higher rates of these components than slower eaters.

Mechanistically, repeated postprandial glucose surges and higher calorie intake promote insulin resistance in muscle and liver cells. Insulin resistance then impairs normal fat storage and increases inflammation, which further worsens metabolic markers. Processed foods, which often accompany fast eating, amplify this effect because they raise glucose levels faster and contain additives that promote overeating.

Risk of Type 2 Diabetes

Your pattern of eating quickly raises your risk for type 2 diabetes through cumulative metabolic strain. Repeated hyperglycemia and insulin resistance stress pancreatic beta cells, reducing their ability to secrete adequate insulin over time. Cohort studies report higher incidence of type 2 diabetes among people who habitually finish meals in under 20 minutes compared with those who take longer.

Fast eating also correlates with weight gain and central adiposity—two strong independent risk factors for type 2 diabetes. If you combine fast eating with frequent consumption of processed, high-glycemic foods, your post-meal glucose excursions become larger and more frequent, accelerating progression from insulin resistance to diabetes.

Practical Strategies to Slow Down Eating

Small, repeatable tactics make the biggest difference: pause between bites, increase chewing, reduce distractions, and use tools that physically limit speed. These changes help your gut start digestion in the mouth, let fullness hormones register, and cut swallowed air that causes bloating.

Mindful Eating Techniques

Mindful eating trains you to notice flavor, texture, and hunger cues so you stop before you feel uncomfortably full. Before you eat, take one deep breath and rate your hunger on a 1–10 scale; this anchors attention and reduces automatic overeating.

During the meal, place your utensils down after each bite. This creates natural pauses for satiety signals—CCK and GLP-1—to rise and reach the brain, which takes about 15–20 minutes. Focus on the taste and texture of each mouthful; savoring flavors gives your brain extra data to judge satisfaction.

Use one simple checklist: breathe, chew, set down utensil, sip water, reassess hunger. Repeat until the habit feels automatic.

Chewing Thoroughly and Taking Smaller Bites

Chewing mechanically breaks food into smaller particles and mixes it with saliva, where amylase and lipase begin digestion. If you chew thoroughly, the stomach receives a pre-digested bolus, reducing workload and lowering reflux and indigestion risk.

Aim for 20–30 chews for dense foods like meat, and at least 10–15 for softer items. Cut food into bite-sized pieces before you start to force smaller bites naturally. Smaller bites slow intake and increase mindful chewing, which increases early release of satiety hormones and improves nutrient absorption.

If you still eat quickly, count chews silently or set a goal like “chew twice as long as usual.” That concrete metric helps form a new rhythm.

Using Smaller Utensils and Meal Timers

Smaller forks, spoons, or chopsticks reduce bite size and automatically slow pace. A smaller utensil means less food per mouthful and forces you to take more deliberate, slower bites.

Set a visible meal timer to at least 20 minutes. Research shows that fullness signals often need that window to develop; a timer prevents racing through a plate before your brain registers satiety. Use a kitchen timer or a phone alarm labeled “pause and breathe” as a behavioral cue.

Combine tools: smaller utensils plus a timer and a rule—no second helpings before 20 minutes—creates structured friction that rewires automatic fast-eating patterns.

Reducing Distractions During Meals

Eating while working, watching screens, or scrolling detaches attention from flavor and fullness cues, so you eat more before satiety registers. Remove the phone, turn off the TV, and eat at a table to reconnect with the meal.

If you must eat at a desk, create micro-rules: close the laptop lid between bites, or eat standing up with no devices for 10 minutes. These small barriers reduce mindless bites and lower swallowed air from impatient gulping.

Track symptoms: if you notice less bloating and fewer reflux episodes after cutting distractions, you’ve reduced swallowed air and improved coordinated digestion between mouth, stomach, and brain.

Factors and Habits Influencing Eating Speed

Multiple forces shape how quickly you eat, from immediate emotions to long‑standing routines and serious eating disorders. These forces change your bite size, chewing, and attention, which directly affect digestion, satiety signaling, and risk of choking.

Emotional and Environmental Triggers

Stress, anxiety, and time pressure speed up your chewing and swallowing. When you feel rushed, your sympathetic nervous system activates, reducing saliva production and slowing the digestive process that normally starts in the mouth. Faster swallowing also increases the amount of air you gulp, which raises bloating and trapped gas.

Environmental cues matter too. Eating while working, watching screens, or standing shortens meal duration and distracts you from fullness signals like stomach distension and hormone changes (GLP‑1, ghrelin). Loud, crowded settings push you to finish quickly to move on, while bright lighting and limited break times create the same effect. You can see measurable digestive effects when attention shifts away from eating: reduced chewing and larger bite sizes lead to poorer nutrient breakdown and higher post‑meal discomfort.

Eating Habits and Learned Behaviors

Your habitual plate size, utensil choice, and bite pattern determine pace. Larger plates and big utensils encourage bigger bites and quicker intake; smaller utensils force slower, smaller bites. Habitual under‑chewing makes the stomach work harder, increasing reflux and indigestion because food enters the stomach less broken down and mixed with saliva enzymes.

Learned routines—eating quickly because parents did it, skipping meals then overeating, or training yourself to finish in a short lunch break—reprogram hunger cues. Over months, the brain associates quick consumption with reward, reducing sensitivity of fullness hormones. Studies show that increasing chew counts and pausing between bites raises GLP‑1 and reduces subsequent snacking, which explains why changing small mechanical habits improves digestion and calorie control.

Disordered Eating Risks

Rapid eating can be a symptom of binge eating, bulimia, or other disordered behaviors where loss of control drives speed. In those cases, fast eating amplifies physiological harm: greater calorie intake, impaired glucose regulation, and repeated gastric overdistension that can blunt satiety signals long term. You also face elevated choking risk if you habitually take large, unchewed bites.

If you eat very quickly and pair it with secrecy, guilt, or extreme restriction between episodes, seek assessment. Clinicians use behavioral history and screening tools to identify disordered patterns because treatment reduces both psychological harm and the digestive consequences of chronic rapid intake. Evidence links fast‑eating behaviors in clinical populations to higher rates of metabolic syndrome and GI complaints, so addressing the underlying disorder improves digestive outcomes.