You’ve probably noticed that during stressful periods, your digestion feels off and your gas smells worse than usual. This isn’t just in your head. When you’re stressed, your body releases cortisol and other hormones that slow digestion, alter gut bacteria composition, and increase intestinal permeability, which directly changes how your body produces and processes gas. The result is often more frequent, more uncomfortable, and notably more odorous gas.

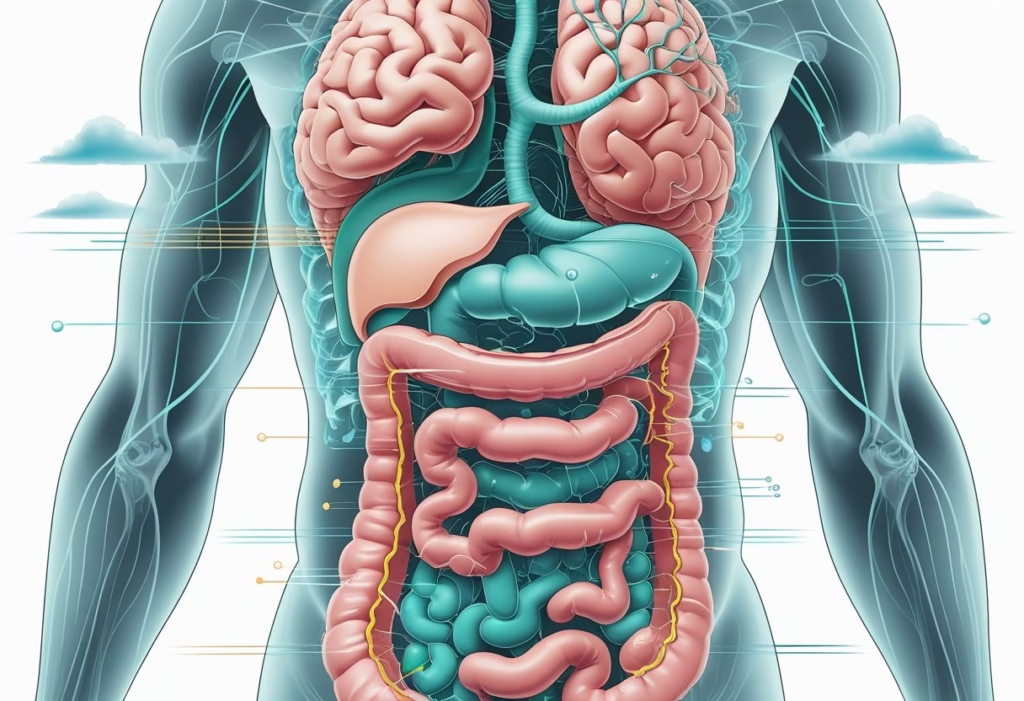

The connection between your mental state and your digestive system runs deeper than most people realize. Your gut contains its own nervous system with millions of neurons that communicate constantly with your brain. When stress activates your fight-or-flight response, it diverts blood flow away from your digestive tract and disrupts the delicate balance of bacteria living in your intestines. These bacteria play a direct role in breaking down food, and when their populations shift under stress, they produce different types and amounts of gas.

Understanding why stress affects your gut and gas smell matters because it changes how you approach the problem. Many people make the mistake of only addressing dietary triggers while ignoring the stress component, or they assume their symptoms are purely anxiety-related when there may be underlying gut issues that stress is worsening. We’ll explore the biological mechanisms behind these changes, explain what specifically makes stress-related gas smell different, and provide evidence-based strategies that address both the digestive and stress components of this issue.

The Gut-Brain Connection: How Stress Impacts Digestion

Your gut and brain maintain constant communication through a sophisticated network of nerves, hormones, and chemical signals. When stress activates your body’s fight-or-flight response, this communication pathway directly alters digestive function, enzyme production, and gut motility in ways that can worsen gas production and odor.

Understanding the Gut-Brain Axis

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system linking your central nervous system with your gastrointestinal tract. This connection operates through three main pathways: neural signals via the vagus nerve, hormonal messages through your bloodstream, and chemical signals produced by gut bacteria.

Your gut contains over 100 million neurons—more than your spinal cord—forming what scientists call the enteric nervous system. This “second brain” produces approximately 95% of your body’s serotonin and about 50% of dopamine, neurotransmitters typically associated with mood but essential for digestive function.

When you experience stress, your brain immediately communicates with your gut through this axis. This explains why anxiety triggers nausea, why nervousness causes diarrhea, and why chronic stress leads to persistent digestive issues. The communication flows both ways: an unhealthy gut sends distress signals to your brain, potentially worsening anxiety and depression.

Common mistake: Many people treat digestive symptoms without addressing underlying stress, which rarely provides lasting relief since the root cause remains active.

The Role of the Vagus Nerve and Enteric Nervous System

The vagus nerve serves as the primary physical connection between your gut and brain, transmitting approximately 80-90% of signals from your gut to your brain (not the reverse). This nerve directly influences stomach acid production, pancreatic enzyme secretion, gallbladder function, and intestinal motility.

When stress activates your sympathetic nervous system, it suppresses vagal tone—the measure of vagus nerve activity. Low vagal tone means reduced digestive capacity: your stomach produces less acid, your pancreas releases fewer enzymes, and food moves more slowly through your intestines. This incomplete digestion creates the perfect environment for bacterial fermentation, producing hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur compounds that smell particularly foul.

Your enteric nervous system controls gut function semi-independently but remains heavily influenced by stress signals. During acute stress, it may speed up gut transit (causing diarrhea), while chronic stress typically slows motility (causing constipation). Both extremes disrupt normal digestion and alter the gut microbiome composition, favoring gas-producing bacteria over beneficial species.

What makes symptoms worse: Eating large meals during stressful periods, since your digestive capacity is already compromised.

Cortisol and the Stress Response on the Gut

Cortisol, your primary stress hormone, directly impacts digestive function in several problematic ways. Elevated cortisol decreases stomach acid production by up to 40%, impairs the intestinal barrier (increasing permeability), and shifts blood flow away from digestive organs toward muscles and the brain.

Chronic cortisol elevation reduces secretory IgA, your gut’s primary immune defense, making you more susceptible to infections and imbalances in gut bacteria. Studies show that prolonged stress increases populations of gas-producing bacteria like Desulfovibrio species, which generate hydrogen sulfide—the compound responsible for the characteristic rotten egg smell.

Your body also produces more inflammatory cytokines under stress, damaging the gut lining and reducing digestive enzyme production. This creates a cycle: poor digestion feeds problematic bacteria, which produce more gas and worsen inflammation, which further impairs digestion.

When to see a doctor: If you experience persistent changes in gas smell accompanied by blood in stool, unintended weight loss, or severe abdominal pain lasting more than a week.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and should not replace professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for persistent or severe digestive symptoms.

Physical Effects of Stress on Your Gut and Gas Smell

Stress triggers a cascade of physical changes in your digestive system that directly affect how your gut processes food and produces gas. The fight-or-flight response diverts blood flow away from digestion, alters the balance of bacteria in your intestines, and changes how quickly food moves through your system—all of which influence both the volume and odor of gas you produce.

Altered Digestion and Gas Production

When you’re stressed, your body releases cortisol and adrenaline, which slow down stomach acid production and reduce digestive enzyme secretion. This means food sits in your stomach longer and doesn’t break down as efficiently when it reaches your intestines.

Partially digested food becomes fuel for gut bacteria, which ferment it and produce hydrogen, methane, and sulfur-containing gases. The less completely your stomach and small intestine digest proteins and carbohydrates, the more material reaches your colon for bacterial fermentation.

Common mistake: Many people eat the same foods during stressful periods and wonder why they suddenly experience more gas. The food isn’t the problem—your compromised digestive capacity is.

Stress also reduces bile flow from your gallbladder, which impairs fat digestion. Undigested fats contribute to both bloating and particularly foul-smelling gas because they’re metabolized by sulfur-producing bacteria in your colon.

Changes in Gut Motility and Bloating

Stress disrupts the rhythmic contractions of your intestines called peristalsis. Some people experience slowed motility (constipation), while others have accelerated transit (diarrhea). Both extremes cause gas problems.

Slowed motility means food ferments longer in your intestines, producing more gas and allowing it to build up. You’ll typically feel bloated, especially after meals, and may notice your abdomen is visibly distended by evening.

Rapid motility prevents proper absorption of nutrients and water, but it also means gas moves through quickly with less time for your body to reabsorb it through the intestinal wall. This often results in urgent bowel movements with excessive gas.

What makes it worse: Eating large meals when stressed overwhelms your already compromised digestive system. Drinking carbonated beverages adds extra gas your gut can’t efficiently process.

What usually helps: Eating smaller portions more frequently gives your stressed digestive system manageable amounts to process. Walking after meals stimulates normal gut motility.

Stress-Induced Changes in Gas Smell

The odor of your gas depends on which bacterial species dominate your gut and what they’re fermenting. Chronic stress shifts your gut microbiome composition, typically reducing beneficial bacteria and allowing sulfur-producing species to proliferate.

Sulfur compounds like hydrogen sulfide create the characteristic rotten egg smell. When stress compromises protein digestion, more amino acids containing sulfur (methionine and cysteine) reach your colon intact, providing raw material for these odorous gases.

Stress-related acid reflux or taking antacids can worsen gas smell by reducing stomach acid too much. Stomach acid is your first line of defense against harmful bacteria, and without it, the wrong bacteria colonize your small intestine—a condition called SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth).

When to see a doctor: If you notice sudden, persistent changes in gas smell combined with weight loss, blood in stool, or severe abdominal pain, consult a healthcare provider. These may indicate conditions beyond stress-related changes.

What rarely helps: Probiotics marketed for general digestive health often don’t address stress-induced microbiome changes. Over-the-counter gas relief products only treat symptoms temporarily without addressing the underlying stress response affecting your digestion.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice. Persistent digestive symptoms require evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider.

Gut Microbiome Disruption: Stress and Bacterial Imbalance

Stress triggers a cascade of changes in your gut bacteria populations, reducing beneficial species while allowing harmful bacteria to flourish. These shifts compromise your intestinal barrier and spark inflammatory responses that can directly affect gas production and odor.

Impact of Stress on Gut Bacteria

When you experience stress, your body releases hormones like cortisol and noradrenaline that directly alter which bacteria can survive in your gut. Research shows that stress hormones stimulate the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli while reducing beneficial species like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.

Stress also slows gut transit time, meaning food sits longer in your digestive tract. This creates an environment where gas-producing bacteria thrive and ferment undigested material more extensively. The result is increased gas volume and changes in the types of gases produced.

Studies of students during exam periods show decreased levels of lactic acid-producing bacteria as academic stress increased. Military personnel undergoing intense physical and psychological stress experienced measurable drops in gut microbiota diversity within just four weeks. The bacteria most affected by stress are often those living closest to your intestinal wall, which play critical roles in maintaining the gut barrier and regulating immune responses.

Gut Dysbiosis and Its Consequences

Gut dysbiosis refers to an imbalance where harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial ones. This imbalance directly affects gas smell because different bacterial species produce different metabolic byproducts during digestion.

Common gas-producing bacteria that increase during dysbiosis:

- Enterococcus species (produce ammonia and sulfur compounds)

- Streptococcus species (generate hydrogen sulfide)

- Certain Clostridium strains (create indole and skatole)

These bacteria break down proteins into particularly foul-smelling compounds. When beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus decline, you lose their protective effects including production of short-chain fatty acids that regulate gut pH and suppress pathogenic bacteria growth.

Dysbiosis also affects bile acid metabolism. Your gut bacteria transform bile acids, and when this process becomes disrupted, it changes how you digest fats. Poor fat digestion leads to increased fermentation and production of malodorous gases. Research on inflammatory bowel disease patients shows those with depression and anxiety have up to 100-fold higher levels of certain bacteria that break down the protective mucus layer.

Role of Inflammation and Leaky Gut

Stress weakens your intestinal barrier by reducing mucus secretion and disrupting tight junctions between intestinal cells. This condition, often called leaky gut or increased intestinal permeability, allows bacteria and bacterial products to contact epithelial cells directly and even translocate into your bloodstream.

When bacteria breach this barrier, your immune system responds with inflammation. This inflammatory response further damages the intestinal lining, creating a self-perpetuating cycle. Studies of soldiers during combat training documented simultaneous increases in intestinal permeability markers, inflammatory molecules, and gastrointestinal symptoms including changes in gas patterns.

Local gut inflammation alters how your intestinal cells function. Inflamed tissue produces less digestive enzymes and absorbs nutrients less efficiently, leaving more material for bacteria to ferment into gas. The inflammatory molecules also change gut motility patterns, sometimes slowing transit and sometimes speeding it unpredictably.

Signs your gas issues may involve inflammation:

- Gas accompanied by abdominal pain or cramping

- Changes in stool consistency alongside gas changes

- Gas that worsens after eating specific foods

- Systemic symptoms like fatigue or joint pain

Healthcare workers experiencing prolonged stress showed reduced gut bacteria diversity that persisted for six months, demonstrating how chronic stress can cause lasting changes. If your gas smell changes persist beyond two weeks or you develop additional symptoms like blood in stool, unexplained weight loss, or severe abdominal pain, consult a gastroenterologist rather than attempting self-treatment.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Persistent gastrointestinal symptoms require evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider.

Stress-Related Gut Disorders and Symptoms

Chronic stress doesn’t just cause temporary digestive discomfort. It can trigger or worsen specific medical conditions that affect how your stomach and intestines function, leading to persistent symptoms that include changes in bowel habits, upper abdominal pain, and increased gas production with altered odor.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Dyspepsia

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 10-15% of adults and becomes significantly worse during stressful periods. Your brain and gut communicate through the vagus nerve, and when stress hormones stay elevated, this connection becomes hypersensitive. You might experience abdominal cramping, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, or alternating between both.

Stress triggers IBS flare-ups because cortisol increases gut permeability and alters how quickly food moves through your intestines. When transit time speeds up, bacterial fermentation becomes incomplete, producing excess hydrogen sulfide gas with a characteristic rotten egg smell. When transit slows down, bacteria have more time to break down proteins, creating stronger-smelling methane and ammonia.

Functional dyspepsia causes upper abdominal pain, early fullness, and nausea without visible damage to your stomach lining. Stress amplifies these symptoms by increasing stomach acid production while simultaneously delaying gastric emptying. This creates a painful contradiction where acid sits longer in your stomach.

Common mistake: Many people restrict their diet severely, thinking food is the primary trigger. While certain foods can worsen symptoms, unmanaged stress often remains the underlying driver. A gastroenterologist can help distinguish between IBS, functional dyspepsia, and other conditions through proper testing rather than guesswork.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Acid Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when stomach acid repeatedly flows back into your esophagus. Stress weakens the lower esophageal sphincter, the muscular valve that keeps acid where it belongs. You’ll feel burning in your chest, regurgitation, and sometimes a sour taste in your mouth.

During stress, your body produces more stomach acid while also increasing sensitivity to normal acid levels. This means you might experience reflux symptoms even when acid production isn’t exceptionally high. Stress also makes you more likely to engage in behaviors that worsen reflux: eating quickly, choosing fatty or spicy foods, drinking alcohol, and lying down soon after meals.

What makes it worse: Shallow breathing during anxiety episodes creates pressure changes in your chest cavity that can pull acid upward. Nighttime stress and poor sleep quality allow acid to damage esophageal tissue for extended periods since you’re lying flat.

When to see a doctor: Reflux occurring more than twice weekly, difficulty swallowing, or weight loss require evaluation by a gastroenterologist to rule out complications like Barrett’s esophagus.

Other Stress-Induced Digestive Issues

Stress causes several additional digestive problems beyond the major disorders. You might experience stress-induced nausea without vomiting, sudden urgent bowel movements, or periods where your stomach feels perpetually unsettled.

Your gut microbiome shifts under chronic stress, with beneficial bacteria declining and inflammatory species increasing. This imbalance produces different gas byproducts than a healthy microbiome would, often with stronger odors. Stress also reduces digestive enzyme production, meaning proteins and fats don’t break down completely before reaching your colon, where bacteria ferment them into foul-smelling gases.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) becomes more likely when stress slows the migrating motor complex, the “housekeeping waves” that sweep bacteria from your small intestine into your colon between meals. Bacteria that don’t belong in your small intestine produce excessive gas, causing bloating within 30-90 minutes after eating.

What usually helps: Addressing the stress response through vagal nerve stimulation techniques (like deep breathing) typically provides more relief than additional dietary restrictions alone. What rarely helps: Over-the-counter gas medications don’t address the underlying stress-microbiome disruption causing malodorous gas in the first place.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice. Persistent digestive symptoms require evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider to rule out serious conditions.

Strategies to Improve Gut Health and Reduce Stress

Targeting both gut health and stress simultaneously addresses the root causes of digestive symptoms and gas odor. Probiotics restore bacterial balance, mindfulness practices regulate the gut-brain axis, and specific lifestyle changes create lasting improvements in both digestion and stress response.

Probiotics and Dietary Approaches

Probiotics help restore beneficial bacteria that stress depletes, particularly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains that reduce gas-producing organisms. Research shows that multi-strain probiotics work better than single strains for stress-related digestive issues because they target multiple bacterial imbalances simultaneously.

You should choose probiotics with at least 10 billion CFUs that include these specific strains. Take them consistently for 4-6 weeks before expecting noticeable changes in gas smell or bloating.

Dietary fiber from vegetables, legumes, and whole grains feeds beneficial bacteria, but adding too much fiber too quickly worsens gas production. Increase fiber gradually by 5 grams per week to allow your gut bacteria to adjust. Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut provide both probiotics and prebiotics, though some people temporarily experience more gas as their microbiome rebalances.

Common mistakes: Taking probiotics irregularly or expecting immediate results. Eating highly processed foods while taking probiotics undermines their effectiveness because additives and artificial sweeteners feed harmful bacteria.

Mindfulness, Meditation, and Stress Management

Mindfulness and meditation directly lower cortisol levels, which reduces gut inflammation and normalizes digestion within 20-30 minutes of practice. Deep breathing activates the vagus nerve, signaling your gut to resume normal motility after stress has slowed or accelerated it.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy shows the strongest evidence for IBS symptoms, with 70% of patients reporting improvement in gas, bloating, and abdominal pain. You need 6-12 sessions with a trained practitioner for lasting results.

Daily meditation for just 10 minutes measurably changes gut bacteria composition after 8 weeks. The practice works because it interrupts the stress-cortisol-inflammation cycle that damages your gut lining and alters bacterial balance.

What rarely helps: Random relaxation apps without structured programs or brief, inconsistent meditation attempts. Stress management requires daily practice to rewire your gut-brain communication.

Lifestyle Habits and Professional Support

Regular exercise improves gut motility and reduces stress hormones, but timing matters. Exercising within 2 hours after eating can worsen gas and bloating. Moderate activity like walking for 30 minutes daily provides gut benefits without triggering digestive distress.

Sleep deprivation increases cortisol and disrupts gut bacteria more than dietary choices. You need 7-8 hours nightly because gut bacteria follow circadian rhythms and restore themselves during sleep.

When to see a gastroenterologist: If gas smell becomes progressively worse despite these strategies, or if you experience weight loss, blood in stool, or severe abdominal pain. Persistent symptoms lasting beyond 3 months with lifestyle changes warrant professional evaluation for conditions like SIBO, inflammatory bowel disease, or pancreatic insufficiency.

A gastroenterologist can order specific tests like breath tests for bacterial overgrowth or stool analysis for digestive enzyme deficiencies that at-home strategies cannot address.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider before starting new supplements or if symptoms persist or worsen.