When you finish a course of antibiotics, you might wonder when your digestive system will feel normal again. The recovery timeline for gut health after antibiotics typically ranges from a few weeks to six months, though some bacterial populations may take up to a year to fully restore, and in certain cases, some beneficial strains may never return to their original levels. This timeline varies significantly based on the type of antibiotic you took, how long your treatment lasted, and your individual health factors.

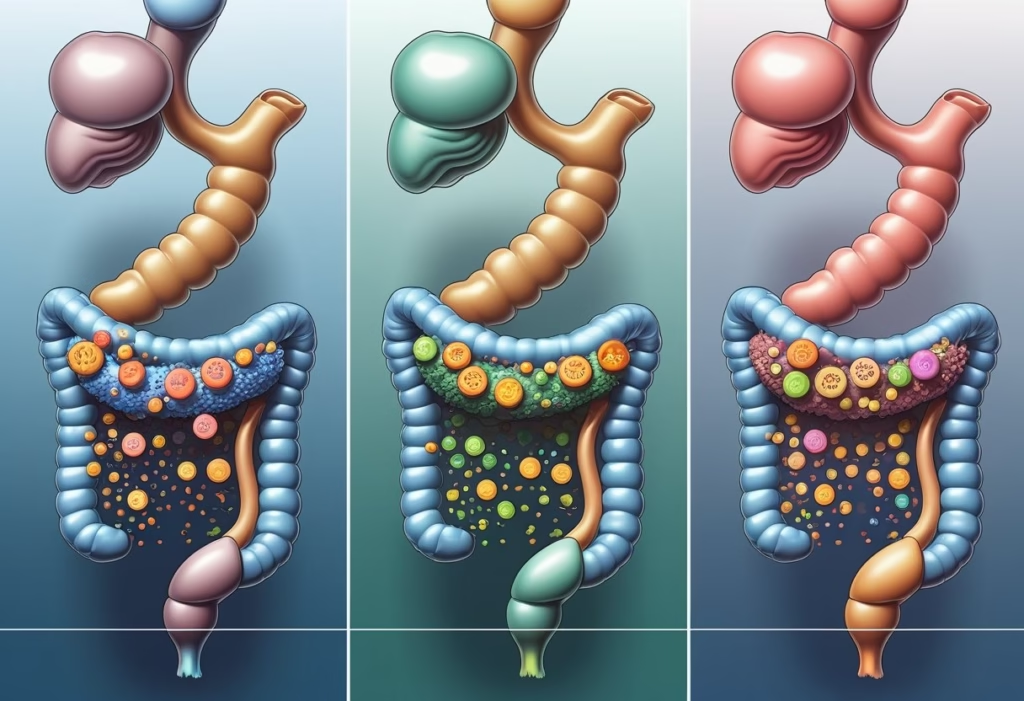

The disruption antibiotics cause goes beyond temporary digestive discomfort. These medications eliminate harmful bacteria causing your infection, but they simultaneously wipe out beneficial microbes that support digestion, immune function, and even mental health. Research shows that broad-spectrum antibiotics create particularly severe disruption, sometimes allowing potentially harmful bacteria to bloom in the absence of their beneficial competitors.

Understanding what happens during each phase of recovery helps you take targeted action to speed healing and avoid common mistakes that delay restoration. You’ll learn why certain symptoms appear at specific times, which dietary strategies actually accelerate recovery versus those that sound helpful but rarely work, and when persistent symptoms signal a need for medical attention. This article examines the science-based timeline of gut microbiome recovery and provides practical approaches to support your digestive system through each stage. This information is for educational purposes and should not replace medical advice from your healthcare provider.

Immediate Effects of Antibiotics on Gut Health

Antibiotics begin altering your gut microbiome within hours of the first dose, triggering a cascade of changes that can reduce bacterial diversity by up to 90% and create an environment where harmful bacteria may thrive. These disruptions often manifest as digestive symptoms within days of starting treatment.

How Antibiotics Disrupt the Microbiome

Antibiotics work by killing bacteria indiscriminately. They cannot distinguish between the harmful pathogens causing your infection and the beneficial bacteria that maintain your gut health.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics cause the most extensive damage because they target a wide range of bacterial species. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics affect fewer bacterial families, but still disrupt the delicate balance of your gut microbiota.

The mechanism is straightforward. Antibiotics interfere with bacterial cell walls, protein synthesis, or DNA replication. Your beneficial gut bacteria use these same biological processes, making them vulnerable to the medication’s effects.

Different antibiotics affect different bacterial populations. Fluoroquinolones and clindamycin tend to cause more severe disruption than penicillins or cephalosporins. The duration of treatment matters too—a three-day course causes less damage than a two-week regimen.

Loss of Microbial Diversity and Balance

Your gut microbiome contains hundreds of bacterial species working in balance. When antibiotics eliminate key species, the entire ecosystem becomes unstable.

Microbial diversity drops rapidly within the first week of antibiotic treatment. Some bacterial families disappear entirely while others decline significantly. This loss creates open niches where opportunistic bacteria can multiply unchecked.

The reduction in diversity weakens your gut’s resilience. A diverse microbiome can resist infections and maintain stability even under stress. When diversity drops, your gut becomes vulnerable to colonization by harmful bacteria like Clostridioides difficile.

Key changes during antibiotic treatment:

- Decreased populations of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species

- Reduced production of short-chain fatty acids

- Weakened intestinal barrier function

- Altered immune signaling in the gut lining

Common Post-Antibiotic Digestive Issues

Digestive symptoms emerge as your disrupted microbiome struggles to perform its normal functions. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea affects 5-35% of people taking antibiotics, depending on the specific medication.

Bloating and gas increase because beneficial bacteria that break down fiber and produce digestive enzymes have been depleted. Food moves through your system differently, and undigested particles can ferment, creating uncomfortable pressure and distension.

Nausea often accompanies antibiotic treatment. This happens partly from direct medication effects on your stomach lining and partly from signals sent by your disrupted gut microbiota to your brain through the gut-brain axis.

When to see a doctor immediately:

- Severe watery diarrhea (more than 6 times daily)

- Blood in stool

- High fever above 101°F (38.3°C)

- Severe abdominal pain or cramping

- Signs of dehydration (dark urine, dizziness, dry mouth)

These symptoms may indicate C. difficile colitis or another serious complication requiring prompt medical attention. Don’t assume all digestive issues during antibiotics are normal—some require urgent intervention.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider about symptoms you experience during or after antibiotic treatment.

Timeline of Gut Microbiome Recovery After Antibiotics

Recovery follows a predictable pattern, though the speed varies based on the antibiotic type, treatment duration, and your baseline health. Most people experience initial recolonization within days, but achieving pre-antibiotic microbiome diversity typically requires months of consistent effort.

Immediate Aftermath: Days 1–7

During the first week after finishing antibiotics, your gut microbiome is at its most depleted state. You might experience loose stools, bloating, or mild cramping as potentially harmful bacteria like enterobacteria temporarily dominate the space left by depleted beneficial strains.

This initial phase often feels worse before it gets better because antibiotics don’t discriminate between harmful pathogens and beneficial bacteria. Your gut lining may be more permeable during this period, which is why some people notice food sensitivities they didn’t have before.

Common symptoms during days 1-7:

- Frequent, loose bowel movements

- Gas and bloating after meals

- Mild abdominal discomfort

- Temporary lactose intolerance

The most common mistake is stopping probiotic-rich foods too soon or eating a low-fiber diet during this critical window. Your remaining beneficial bacteria need fuel to multiply, so continuing prebiotics actually helps despite temporary gas.

Recolonization and Diversification: Weeks 2–4

Beneficial bacteria begin re-establishing during weeks 2-4, though microbiome diversity remains significantly lower than your baseline. You should notice digestive symptoms gradually improving, with more formed stools and less bloating.

This phase is when dietary choices have the greatest impact on recovery speed. Studies show that people who consume fermented foods and diverse fiber sources during this period recover faster than those eating a standard Western diet.

What typically helps:

- Eating 30+ different plant foods per week

- Daily fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut)

- Consistent meal timing

What rarely helps:

- Aggressive probiotic megadosing

- Eliminating all fiber due to gas

- Expecting symptom-free days immediately

Some people experience intermittent symptom flares during this phase as different bacterial populations compete for dominance. This is normal and doesn’t indicate you’re doing something wrong.

Full Restoration: 1–6 Months

Research indicates recovery can take months or even years to achieve your original species composition. Most people see substantial improvement by 2-3 months, but some beneficial strains may never fully return without targeted intervention.

The timeline for full restoration depends heavily on whether you had a healthy baseline microbiome before antibiotics. If you took multiple antibiotic courses in the past year or have underlying digestive issues, restoration takes longer.

By month 3-6, your microbiome diversity should approach 70-90% of pre-antibiotic levels if you’ve maintained gut-supportive habits. However, certain keystone species that were completely eliminated may not spontaneously return without reintroduction through fermented foods, probiotics, or environmental exposure.

Medical disclaimer: If you still have significant digestive symptoms after 6-8 weeks, consult a gastroenterologist to rule out conditions like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or Clostridioides difficile infection.

Factors Influencing Recovery Duration

| Factor | Impact on Recovery |

|---|---|

| Antibiotic type | Broad-spectrum antibiotics (fluoroquinolones, clindamycin) cause more extensive damage than narrow-spectrum options |

| Treatment duration | Each additional week of antibiotics extends recovery time by approximately 2-3 weeks |

| Baseline diversity | People with robust pre-antibiotic microbiomes recover 40-50% faster |

| Dietary fiber intake | Less than 20g daily fiber can double recovery time |

| Previous antibiotic exposure | Multiple courses within 12 months create cumulative damage |

Age significantly affects how long it takes to restore good bacteria after antibiotics, with adults over 65 experiencing slower recovery due to reduced microbiome resilience. Children under 3 are particularly vulnerable because their microbiomes are still developing.

Stress and poor sleep actively suppress beneficial bacteria growth, which explains why people with demanding jobs or sleep disorders often report prolonged digestive issues after antibiotics. Your gut bacteria follow circadian rhythms, so irregular sleep schedules disrupt their recolonization patterns.

See a doctor if you experience:

- Watery diarrhea with fever or blood

- Severe abdominal pain that worsens

- Unintentional weight loss exceeding 5% of body weight

- Symptoms persisting beyond 8 weeks despite dietary interventions

Dietary Strategies to Restore Gut Health

Your diet directly influences which bacteria thrive in your gut after antibiotics deplete beneficial species. Strategic food choices can accelerate recovery by feeding helpful bacteria and introducing live cultures that colonize your digestive tract.

Probiotic-Rich Foods and Supplements

Fermented foods naturally contain live beneficial bacteria that can help repopulate your gut. Yogurt with live active cultures provides Lactobacillus species, while kefir offers a broader range of bacterial strains plus beneficial yeasts. Sauerkraut and kimchi deliver diverse bacterial communities that survive stomach acid better than many supplements.

Research shows specific probiotic strains like Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii have demonstrated effectiveness in clinical studies. If choosing a probiotic supplement, look for multi-strain products with 10-50 billion colony-forming units.

A common mistake is starting probiotics too early. Some evidence suggests waiting until after you complete antibiotics may be more beneficial than taking them concurrently, as antibiotics can kill the probiotic bacteria before they establish themselves.

What usually helps: Daily fermented food consumption combined with targeted probiotic strains

What rarely helps: Single-strain probiotics with low CFU counts or products without refrigeration requirements

Note: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before starting new supplements, especially if you have compromised immunity.

Incorporating Prebiotic-Rich Foods

Prebiotics are plant fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria, helping them multiply and produce health-promoting compounds. Your recovering gut needs these foods because they selectively nourish helpful species while starving harmful bacteria.

Bananas contain resistant starch and inulin that specifically feed Bifidobacterium species. Oats provide beta-glucan fiber that supports multiple bacterial strains. Garlic and onions are rich in fructooligosaccharides that promote Lactobacillus growth. Apples deliver pectin, a soluble fiber that beneficial bacteria ferment into short-chain fatty acids.

The mistake most people make is focusing solely on probiotics while neglecting prebiotics. Without adequate prebiotic fiber, even the best probiotic bacteria cannot establish permanent colonies because they lack food to survive.

Key prebiotic sources:

- Garlic and onions (raw is more potent)

- Bananas (slightly green contain more resistant starch)

- Oats and whole grains

- Apples with skin

- Asparagus and artichokes

Importance of Fiber and Plant Diversity

Plant fibers are essential because different bacterial species consume different types of fiber. Eating fiber-rich foods supports the regrowth of beneficial bacteria throughout your digestive system. Aim for 25-35 grams daily from varied sources.

Diversity matters more than quantity. Each plant food feeds specific bacterial groups, so eating 30+ different plant foods weekly creates more microbial diversity than eating large amounts of just a few foods. Include vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds.

A critical mistake is increasing fiber too quickly, which worsens bloating and gas. Start with small portions and gradually increase over 2-3 weeks as your gut bacteria adjust.

When to see a doctor: If severe bloating, abdominal pain, or diarrhea persists beyond 4-6 weeks despite dietary changes, or if you develop fever or bloody stools.

What makes symptoms worse is processed foods and added sugars, which feed potentially harmful bacteria that may have overgrown during antibiotic treatment.

Lifestyle Habits That Support Gut Restoration

Managing stress, maintaining regular physical activity, and avoiding harmful substances like excessive alcohol and cigarettes directly influence how quickly your gut microbiome recovers after antibiotic treatment. These factors work through the gut-brain axis and affect inflammation levels throughout your digestive system.

Stress Management and Sleep

Chronic stress actively delays microbiome recovery by increasing inflammation and disrupting the balance between beneficial and harmful bacteria. When you experience stress, your body releases cortisol, which alters gut permeability and reduces the diversity of bacterial species trying to reestablish themselves.

Your sleep quality directly affects gut restoration. Poor sleep patterns disrupt circadian rhythms that regulate digestive function and bacterial growth cycles. Aim for 7-9 hours of consistent sleep each night, going to bed and waking at the same times.

Common mistakes include:

- Checking phones before bed, which disrupts melatonin production

- Consuming caffeine after 2 PM

- Ignoring persistent stress without seeking support

Meditation, deep breathing exercises, and progressive muscle relaxation help lower cortisol levels. Stress reduction techniques support gut health by maintaining the gut-brain axis connection. If you experience ongoing anxiety, insomnia lasting more than two weeks, or stress-related digestive symptoms, consult a healthcare provider.

Physical Activity and Hydration

Regular exercise increases microbial diversity and supports the growth of bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids, which reduce inflammation. Physical activity improves gut motility and strengthens the intestinal barrier damaged by antibiotics.

You need at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity weekly. Walking, cycling, swimming, or strength training all benefit gut recovery. Exercise timing matters less than consistency, though intense workouts on an empty stomach may temporarily increase gut permeability.

Proper hydration helps beneficial bacteria colonize your intestinal lining. Water supports mucus production that protects gut tissue and aids in moving fiber through your digestive tract. Drink 8-10 glasses daily, increasing intake during exercise.

What rarely helps: Extreme exercise programs or athletic training during early recovery can increase stress hormones and inflammation. Overhydration dilutes digestive enzymes without added benefit.

Impact of Smoking and Alcohol

Smoking delays gut recovery by reducing blood flow to intestinal tissue and altering the pH balance that beneficial bacteria need. Cigarette toxins promote harmful bacterial species and increase intestinal permeability, worsening post-antibiotic inflammation.

Alcohol disrupts microbiome restoration even in small amounts during the first 4-6 weeks after antibiotics. It damages the gut lining, feeds potentially harmful bacteria, and interferes with the recolonization of beneficial strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species.

Moderate alcohol consumption (1-2 drinks weekly) may be acceptable after the initial recovery period, but daily drinking significantly impairs restoration. Red wine contains polyphenols that may support some beneficial bacteria, but the alcohol content still causes net harm during recovery.

When to see a doctor: If you cannot reduce alcohol intake despite wanting to, or if you experience withdrawal symptoms when trying to quit smoking or drinking, seek professional guidance before these habits further compromise your recovery.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before making significant lifestyle changes, especially if you have underlying health conditions.

Foods and Habits That Delay Recovery

Certain dietary choices directly interfere with beneficial bacteria regrowth and prolong gut inflammation after antibiotic treatment. Processed sugars feed harmful bacteria, high-fat foods slow digestive healing, and ultra-processed items lack the nutrients your microbiome needs to rebuild.

Processed Sugars and Artificial Sweeteners

Processed sugars create an environment where harmful bacteria and yeast thrive at the expense of beneficial species. When you consume high amounts of refined sugar, you’re essentially feeding the wrong microorganisms in your gut. This can lead to an overgrowth of Candida and other problematic species that antibiotics may have left behind.

Artificial sweeteners like aspartame and sucralose are particularly problematic. Research shows these compounds can alter gut bacteria composition and reduce beneficial bacterial diversity. Your gut struggles to recover when these sweeteners continuously disrupt the microbial balance you’re trying to restore.

Common sources to avoid include:

- Sodas and sweetened beverages

- Packaged desserts and baked goods

- Flavored yogurts with added sugar

- Sugar-free products containing artificial sweeteners

The inflammation caused by excess sugar intake also weakens your intestinal barrier, making it harder for your gut lining to heal.

High-Fat and Fried Foods

High-fat foods, particularly those containing saturated and trans fats, slow down gut recovery by promoting inflammation and reducing beneficial bacteria populations. Fried foods are especially damaging because they contain oxidized fats that stress your digestive system when it’s already compromised.

Your body requires more bile acids to digest heavy, fatty meals. This puts additional strain on your liver and digestive tract during a period when they need to focus on healing. The excessive fat content also slows gastric emptying, which can worsen symptoms like bloating and nausea that often accompany antibiotic use.

Fast food, deep-fried items, and processed meats contain compounds that directly suppress the growth of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria—two bacterial groups essential for gut health restoration. You should avoid calcium-fortified foods as well, since calcium can interfere with antibiotic absorption if you’re still taking medication.

The Role of Ultra-Processed Foods

Ultra-processed foods lack the fiber, polyphenols, and nutrients that beneficial gut bacteria need to flourish. These products typically contain emulsifiers, preservatives, and additives that directly harm your microbiome composition. The manufacturing process strips away the natural compounds that would otherwise support bacterial diversity.

Ultra-processed foods to limit:

- Packaged snack foods and chips

- Instant noodles and meals

- Processed cheese products

- Reconstituted meat products

- Mass-produced bread and pastries

These items often combine multiple problematic elements: refined sugars, unhealthy fats, artificial additives, and minimal fiber. Your recovering gut needs whole, minimally processed foods that contain prebiotics and polyphenols. Polyphenol-rich foods like berries, green tea, and dark chocolate support beneficial bacteria, but you won’t find meaningful amounts in ultra-processed alternatives.

The absence of dietary fiber in these products means your gut bacteria lack the fuel they need for regrowth. Without adequate fiber, beneficial species cannot produce short-chain fatty acids that help repair your intestinal lining.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before making significant dietary changes, especially if you experience persistent digestive symptoms after antibiotic use.

Optimizing Long-Term Gut Health After Recovery

Once your microbiome has recovered from antibiotic disruption, specific dietary and lifestyle patterns become essential for preventing future imbalances and maintaining the resilience you’ve rebuilt. Prioritizing microbial diversity through targeted food choices and establishing sustainable eating patterns will protect against the gradual erosion of beneficial bacteria that often occurs with typical Western diets.

Maintaining Microbial Diversity

Your gut contains hundreds of bacterial species, and maintaining this diversity protects you from future disruptions better than simply increasing the population of a few beneficial strains. Each bacterial species performs distinct functions, from producing specific vitamins to breaking down different types of fiber.

Polyphenols stand out as particularly effective for supporting diverse bacterial populations. These plant compounds feed beneficial bacteria while inhibiting harmful ones. Berries, dark chocolate, green tea, and extra virgin olive oil provide concentrated sources. Research shows polyphenols increase Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus populations while reducing inflammatory bacteria.

Rotating your fiber sources prevents dominance by single bacterial species. If you eat only wheat bran, for example, you’ll favor bacteria that specialize in that fiber type while others diminish. Instead, cycle through oats, legumes, flaxseeds, and resistant starch from cooled potatoes or rice throughout the week.

A common mistake is relying solely on probiotic supplements after initial gut health recovery after antibiotics ends. While helpful during recovery, long-term diversity requires feeding your existing bacteria through varied plant foods rather than continuously adding the same few strains. Most probiotic supplements contain only 5-10 species, while your gut should harbor 500-1000 different types.

Routine Dietary Patterns for Gut Wellness

Your daily eating patterns exert more influence on your microbiome than occasional healthy meals. Consistency matters because bacterial populations shift within 24-48 hours based on available nutrients.

Leafy greens deserve particular attention because they contain sulfoquinovose, a unique sugar molecule that specifically feeds protective bacteria like Akkermansia muciniphila. This species strengthens your intestinal barrier and reduces inflammation. Aim for at least one cup of cooked or two cups of raw greens daily, including spinach, kale, arugula, or Swiss chard.

Intermittent fasting periods of 12-14 hours overnight allow beneficial bacteria to feed on your gut mucus layer, which stimulates mucus production and strengthens your intestinal lining. Eating constantly deprives these bacteria of this maintenance period.

What usually helps:

- Eating 30+ different plant foods weekly

- Including fermented foods 3-4 times per week

- Limiting emulsifiers in processed foods

What rarely helps:

- Expensive “gut health” supplements without dietary changes

- Eliminating entire food groups without medical necessity

- Following restrictive diets long-term

Contact your gastroenterologist if you experience persistent bloating, changes in bowel habits, or digestive discomfort lasting beyond two weeks despite dietary improvements, as these may indicate conditions requiring medical evaluation beyond basic steps for restoring gut health.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is educational and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before making significant dietary changes or if you have persistent digestive symptoms.