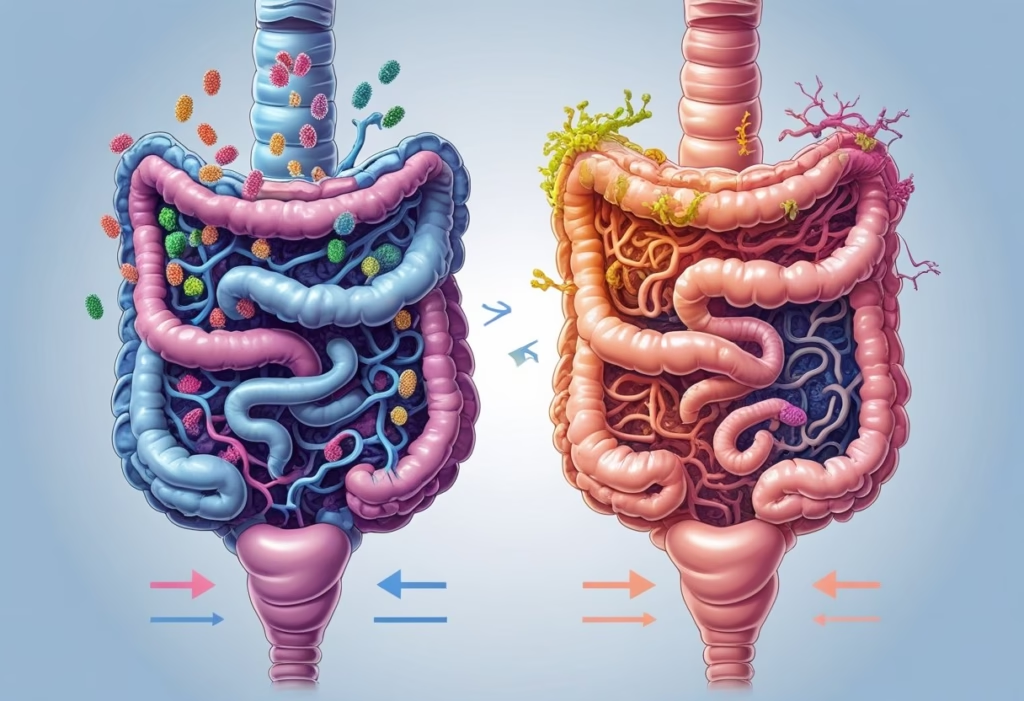

Many people experiencing digestive issues hear terms like gut dysbiosis and IBS thrown around interchangeably, but they’re not the same thing. Gut dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the bacteria living in your digestive tract, while IBS is a functional disorder characterized by chronic symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits. Understanding this distinction matters because it affects how you approach treatment and what you can realistically expect from different interventions.

The confusion makes sense because dysbiosis often plays a role in causing IBS symptoms. Research shows that people with IBS frequently have altered gut bacteria compared to healthy individuals, with lower levels of beneficial bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and higher levels of potentially problematic bacteria like E. coli. However, you can have gut dysbiosis without IBS, and some people with IBS may not have significant bacterial imbalances at all.

The relationship between these two conditions is more complex than a simple cause-and-effect. Factors like food poisoning, antibiotics, chronic stress, and dietary patterns can trigger dysbiosis, which may then contribute to IBS symptoms through mechanisms like increased gut permeability and altered pain sensitivity. Getting clear on what’s happening in your body helps you work with your healthcare provider to target the actual problem rather than just managing symptoms indefinitely.

Defining Gut Dysbiosis and IBS

Gut dysbiosis and IBS are distinct but interconnected conditions that affect digestive health. Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in your gut bacteria, while IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder diagnosed by specific symptoms.

What Is Gut Dysbiosis?

Gut dysbiosis means you have an imbalance in the types and amounts of microorganisms living in your digestive tract. This can manifest in three ways: loss of beneficial bacteria, overgrowth of potentially harmful organisms, or reduced microbial diversity.

Your gut contains approximately 500-1,000 different bacterial species, with total counts reaching around 100 trillion microbes. In a healthy state, over 90% of these belong to four main groups: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria.

Common causes of dysbiosis include:

- Antibiotic use (kills both harmful and beneficial bacteria)

- Poor diet high in processed foods

- Chronic stress

- Environmental toxins

- Excessive alcohol consumption

Dysbiosis often develops gradually. You might not notice symptoms immediately, but over time it can lead to digestive issues, weakened immunity, and inflammation. The condition creates an environment where harmful bacteria can flourish while beneficial species like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium decline in number.

What Is Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)?

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain and altered bowel habits without identifiable structural damage to your intestines. It affects 10-25% of people in the United States and requires symptom-based diagnosis.

The Rome IV criteria classify IBS into four subtypes based on your predominant bowel pattern: IBS-C (constipation-predominant), IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant), IBS-M (mixed), and IBS-U (unsubtyped). You’re diagnosed when recurrent abdominal pain occurs at least one day per week for three months, associated with changes in stool frequency or appearance.

Unlike dysbiosis, IBS is a diagnosed medical condition with specific criteria. Your doctor rules out other diseases through imaging and endoscopy before confirming IBS. The condition significantly impacts quality of life, work productivity, and daily functioning.

IBS symptoms typically worsen with:

- Stress and anxiety

- Certain foods (varies by individual)

- Hormonal changes

- Sleep disruption

- Large meals

The Role of the Gut Microbiome in Health

Your gut microbiome comprises all microorganisms in your intestines, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa. Bacteria make up over 99% of this ecosystem and perform essential functions that extend far beyond digestion.

Beneficial bacteria synthesize vitamins, produce essential amino acids, and facilitate absorption of minerals like iron, magnesium, and zinc. They break down dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which maintain your intestinal barrier integrity and regulate immune function. These organisms also prevent harmful bacteria from colonizing by competing for nutrients and space.

When your microbiome functions properly, it supports gut barrier integrity, produces neurotransmitters that communicate with your brain, and trains your immune system to distinguish between harmless and dangerous substances. Bacteroides, Clostridium, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus species dominate a healthy gut and maintain this balance.

Your microbiome responds dynamically to diet, medication, stress, and environmental factors. Even short-term changes in what you eat can shift bacterial populations within 24-48 hours. This sensitivity explains why your microbiome composition differs significantly from other people’s, even within the same household.

Medical Note: This information is for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of digestive conditions.

How Gut Dysbiosis and IBS Are Related

Dysbiosis disrupts the balance of gut bacteria, which triggers many IBS symptoms through metabolic changes, immune activation, and nervous system signaling. Research shows that 10-25% of people in the United States have IBS, and many of them exhibit measurable changes in their gut microbiome composition compared to healthy individuals.

Links Between Dysbiosis and IBS Symptoms

When your gut bacteria become imbalanced, they produce different metabolites that directly affect how your intestines function. Studies show that people with IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant) have lower levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, while Enterobacteriaceae levels increase significantly.

This shift matters because beneficial bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that maintain your intestinal lining and regulate motility. When these bacteria decline, your gut barrier weakens, allowing bacterial components like lipopolysaccharides to activate inflammatory pathways through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). This creates a cycle where inflammation increases gut sensitivity, leading to abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.

Your symptoms can worsen after infections because pathogenic bacteria often remain elevated long after the initial illness resolves. This is called post-infection IBS. The overgrowth of facultative bacteria thrives in the inflamed gut environment, perpetuating bloating, gas, and irregular bowel movements.

Common mistakes include assuming all probiotics help equally or that antibiotics always worsen dysbiosis. Some antibiotics like rifaximin can actually reduce problematic bacterial overgrowth in specific IBS cases.

Gut Microbiota Diversity and its Impact

Your microbiome diversity refers to the variety of bacterial species in your gut. Healthy individuals typically have 500-1,000 different species, dominated by four phyla: Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria.

IBS patients consistently show reduced diversity and increased Proteobacteria abundance. Meta-analyses confirm that IBS-C (constipation-predominant) patients have significantly higher Bacteroides levels, while IBS-D patients show elevated pathogenic bacteria. Lower diversity means your gut has fewer resources to produce essential metabolites and maintain barrier integrity.

The reduction in bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is particularly problematic because this species has strong anti-inflammatory properties. When it declines, your gut becomes more susceptible to immune dysfunction and increased permeability.

What makes diversity worse: repeated antibiotic courses without probiotic support, highly processed diets low in fiber, chronic stress, and lack of dietary variety. What helps: gradually increasing fiber intake through varied plant sources, though some people need low-FODMAP approaches initially before reintroducing diversity.

The Gut-Brain Axis Connection

The vagus nerve connects your gut and brain through a bidirectional communication pathway called the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Your gut bacteria influence this pathway by producing neurotransmitters, metabolites, and inflammatory signals that reach your central nervous system.

Dysbiosis affects serotonin (5-HT) production since 90% of your body’s serotonin is made in the gut. IBS-D patients show significantly elevated 5-HT and 5-HT3 receptor levels in intestinal tissue, which explains why these individuals experience urgent bowel movements and visceral hypersensitivity. The altered bacterial composition changes tryptophan metabolism, disrupting normal serotonin regulation.

This connection explains why anxiety and depression frequently occur alongside IBS. Bacterial metabolites can cross into circulation and affect brain function, causing brain fog, fatigue, and mood disturbances. The inflammation from dysbiosis activates immune cells that release cytokines, which signal the brain and alter neurotransmitter production.

When to see a doctor: if you experience unexplained weight loss, blood in stool, severe pain that wakes you at night, or symptoms that began after age 50. These suggest conditions beyond functional IBS.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of IBS or suspected dysbiosis.

Key Differences Between Gut Dysbiosis and IBS

Gut dysbiosis represents an imbalance in your intestinal microorganisms, while IBS is a diagnosed functional gastrointestinal disorder with specific symptom criteria. Dysbiosis can exist as an underlying condition that may contribute to IBS, but you can have one without the other.

Causes and Risk Factors

Gut dysbiosis develops when your microbial balance shifts due to specific triggers. Antibiotics are one of the most common causes, as they eliminate both beneficial and harmful bacteria without discrimination. A single course of broad-spectrum antibiotics can disrupt your microbiome for months.

Other causes include dietary factors like high sugar intake, chronic stress, frequent use of proton pump inhibitors, and gastrointestinal infections. Environmental toxins and excessive alcohol consumption also contribute to microbial imbalance.

IBS has different risk factors. Post-infectious IBS can develop after severe gastroenteritis when your gut fails to recover properly. This accounts for approximately 10% of IBS cases. Psychological stress, food intolerance, and altered gut motility are significant contributors. Women are twice as likely to develop IBS compared to men, suggesting hormonal influences play a role.

A key mistake is assuming antibiotics only cause temporary digestive issues. The microbial disruption can persist long after treatment ends, potentially triggering conditions like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Distinctive Symptoms

Symptoms of dysbiosis often manifest systemically beyond your digestive tract. You might experience:

- Brain fog and difficulty concentrating

- Skin problems like eczema or acne

- Frequent yeast infections

- Food intolerances that weren’t present before

- Fatigue unrelated to sleep quality

- Bloating that worsens throughout the day

IBS presents with Rome IV diagnostic criteria: recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week in the last three months, associated with changes in stool frequency or form. The pain typically improves after bowel movements.

The location of discomfort differs. Dysbiosis-related bloating tends to be diffuse and increases with meals. IBS pain is more often cramping and localized to specific abdominal quadrants, particularly the lower left side.

What makes IBS worse: high-FODMAP foods, stress, and hormonal changes during menstruation. What rarely helps: eliminating entire food groups without proper testing, as this can worsen nutritional status and microbial diversity.

Location and Mechanism Differences

Dysbiosis occurs at the microbial level throughout your gastrointestinal tract. The imbalance can happen in your small intestine (as with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth), colon, or both simultaneously. This causes malabsorption when bacteria consume nutrients before your body can absorb them.

The mechanism involves increased populations of pathogenic bacteria like Enterobacteriaceae and reduced beneficial species like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These shifts disrupt your intestinal barrier function by affecting tight junction proteins such as ZO-2 and Occludin.

IBS operates through functional mechanisms rather than microbial ones. Your gut-brain axis becomes hypersensitive, causing visceral hypersensitivity where normal intestinal sensations feel painful. Gut motility becomes dysregulated—either too fast (causing diarrhea) or too slow (causing constipation).

While dysbiosis may contribute to IBS development, IBS diagnosis doesn’t require proven dysbiosis. You can have IBS with a relatively balanced microbiome if other mechanisms like visceral hypersensitivity dominate.

Testing and Diagnosis Methods

Dysbiosis requires direct measurement of your gut microbiome. A comprehensive stool test analyzes bacterial composition, diversity, and the presence of beneficial versus pathogenic organisms. These tests measure specific bacterial phyla like Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria.

A breath test can identify small intestinal bacterial overgrowth by measuring hydrogen and methane gases after consuming lactulose or glucose. Elevated gases indicate bacterial fermentation occurring in your small intestine rather than your colon.

IBS diagnosis follows a symptom-based approach without requiring microbiome testing. Your doctor excludes inflammatory bowel disease through colonoscopy, rules out celiac disease with blood tests, and confirms symptom patterns match Rome IV criteria.

When to see a doctor: if you have unexplained weight loss, blood in stool, severe pain that wakes you at night, or symptoms starting after age 50. These suggest conditions more serious than IBS or dysbiosis.

A common mistake is ordering expensive microbiome tests before trying basic interventions. Start with a food and symptom diary to identify triggers, as this often provides more actionable information than microbiome analysis.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a qualified healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal conditions.

Overlapping and Unique Symptoms

Both gut dysbiosis and IBS produce digestive symptoms that can feel nearly identical, but each condition also has distinct patterns that help differentiate them. Understanding where symptoms overlap and where they diverge helps identify what’s happening in your gut.

Digestive Discomfort and Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain appears in both conditions but for different reasons. With IBS, your pain typically follows a pattern linked to bowel movements—it often improves after you go to the bathroom. The pain stems from abnormal gut contractions and heightened pain sensitivity in your intestinal nerves.

Gut dysbiosis causes abdominal pain through a different mechanism. The imbalance of bacteria produces excess gas and inflammatory compounds that irritate your intestinal lining. This pain doesn’t necessarily improve with bowel movements and may feel more constant or widespread.

Key differences:

- IBS pain often occurs in the lower abdomen and follows eating

- Dysbiosis pain can appear anywhere in your digestive tract

- IBS symptoms worsen with stress; dysbiosis symptoms worsen after eating certain foods that feed harmful bacteria

You should see a doctor if your pain is severe, wakes you at night, or comes with unexplained weight loss. These signs suggest something beyond typical IBS or dysbiosis.

Bloating, Gas, and Constipation

Bloating and gas affect roughly 75% of people with either condition. In dysbiosis, harmful bacteria ferment undigested food and produce excessive hydrogen or methane gas. You’ll notice your bloating worsens after meals, especially those high in fermentable carbohydrates.

IBS-related bloating comes from both gas production and how your gut handles that gas. Your intestines may be hypersensitive, making normal amounts of gas feel uncomfortable. Methane-producing bacteria (often present in dysbiosis) slow gut movement, leading to constipation in both conditions.

Constipation appears differently depending on the cause. IBS constipation alternates with other bowel patterns and responds to stress. Dysbiosis-related constipation stays more consistent and improves when you address the bacterial imbalance.

What makes symptoms worse:

- High FODMAP foods (onions, garlic, beans)

- Artificial sweeteners

- Carbonated drinks

- Eating too quickly

Probiotics containing Bacillus coagulans help some people with IBS, while targeted antibiotics like rifaximin work better for dysbiosis-driven symptoms.

Diarrhea and Stool Changes

Diarrhea occurs in both conditions but has different triggers and characteristics. IBS diarrhea typically happens in the morning or after meals and rarely wakes you at night. You’ll experience urgency and may have multiple loose stools in quick succession, followed by normal periods.

Dysbiosis produces diarrhea when harmful bacteria damage your intestinal lining and increase its permeability. This creates inflammation and draws water into your intestines. The diarrhea feels less predictable than IBS and may include undigested food particles or mucus.

Stool appearance differences:

| Condition | Common Stool Characteristics |

|---|---|

| IBS | Loose, watery; pencil-thin during constipation phases; mucus present |

| Dysbiosis | Greasy or foul-smelling; undigested food visible; color changes |

SIBO symptoms (a specific type of dysbiosis) include particularly foul-smelling diarrhea and fatty stools. This happens because bacteria in your small intestine break down fats before your body absorbs them properly.

See a doctor immediately if you notice blood in your stool, black or tar-like stools, or persistent diarrhea lasting more than two weeks. These symptoms suggest conditions requiring different treatment approaches.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for proper diagnosis and treatment of digestive symptoms.

Associated Conditions and Complications

Both gut dysbiosis and IBS can trigger or worsen other health conditions beyond digestive symptoms. Bacterial overgrowth patterns differ from general dysbiosis, while inflammation risk varies between these conditions, and effects can extend to skin, energy levels, and mental function.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO occurs when bacteria overgrow in your small intestine rather than staying primarily in your colon. This creates a distinct pattern from general gut dysbiosis, which refers to microbial imbalances throughout your entire digestive tract.

You’re more likely to develop SIBO if you have IBS, particularly IBS-D (diarrhea-predominant). Studies show 30-40% of IBS patients test positive for SIBO. The connection exists because slowed gut motility—common in IBS—allows bacteria to accumulate where they shouldn’t be.

SIBO symptoms overlap heavily with IBS: bloating within 30-90 minutes after eating, gas, abdominal pain, and altered bowel movements. The key difference is timing. SIBO bloating typically occurs shortly after meals, while general IBS bloating can happen at any time.

Common mistake: Taking probiotics when you have SIBO can worsen symptoms. More bacteria in your system isn’t helpful when the problem is bacteria in the wrong location.

A breath test measuring hydrogen and methane gas can diagnose SIBO. Your doctor may recommend this test if standard IBS treatments aren’t working or if you have specific risk factors like previous abdominal surgery, diabetes, or chronic use of medications that slow gut motility.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Other Risks

Gut dysbiosis plays a documented role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These are distinct from IBS—they involve actual tissue damage and inflammation visible on scopes and scans.

Research shows people with IBD have reduced microbial diversity, with decreases in beneficial bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and increases in Proteobacteria. This imbalance doesn’t cause IBD directly, but it worsens inflammation and can trigger flares. The relationship is bidirectional: dysbiosis promotes inflammation, and inflammation further disrupts your microbiome.

When to see a doctor: Blood in stool, unintended weight loss, persistent severe pain, or fever alongside digestive symptoms suggest IBD rather than IBS. These require immediate medical evaluation.

Long-term gut dysbiosis may increase risk for metabolic conditions including diabetes and obesity. Altered bacterial populations affect how your body processes nutrients and regulates blood sugar. Some studies link specific dysbiosis patterns to colorectal cancer risk, though this connection requires more research to establish clear causation.

Non-Digestive Manifestations

Your gut microbiome influences systems throughout your body through the gut-brain axis, immune signaling, and metabolite production. When dysbiosis occurs, effects can appear far from your digestive tract.

Chronic fatigue is common in both gut dysbiosis and IBS. The mechanism involves reduced production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, which your cells need for energy. Inflammatory signals from an imbalanced gut also drain your energy reserves.

Acne and other skin conditions can worsen with gut dysbiosis. Your skin microbiome responds to changes in your gut bacterial composition. When harmful bacteria produce more inflammatory compounds, these travel through your bloodstream and trigger skin inflammation. This is why some people notice their acne improves when treating gut issues.

Mental health symptoms—anxiety and depression—frequently accompany IBS and dysbiosis. Your gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA, and dysbiosis disrupts this production. Brain fog, difficulty concentrating, and mood changes often improve when gut balance is restored.

What usually helps: Addressing the underlying dysbiosis through targeted dietary changes, specific probiotics (strain matters), and treating any infections. What rarely helps: Random supplements without identifying your specific imbalances, or ignoring persistent symptoms hoping they’ll resolve on their own.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of any health condition.

Diagnosis and Treatment Approaches

Testing methods differ significantly between gut dysbiosis and IBS, with dysbiosis requiring direct microbiome assessment while IBS remains a clinical diagnosis based on symptoms. Treatment strategies overlap considerably, though targeting the underlying microbial imbalance often addresses both conditions simultaneously.

Testing for Gut Dysbiosis and IBS

Your doctor diagnoses IBS primarily through your symptom history, not through specific tests. You need to experience recurrent abdominal pain at least one day per week for the past three months, associated with changes in stool frequency or appearance. Testing serves mainly to exclude other conditions—particularly celiac disease in all patients and inflammatory bowel disease in those with diarrhea.

Stool analysis provides the most accessible way to assess gut dysbiosis. These tests identify bacterial populations, though they have important limitations. Stool samples represent only what passes through your colon, not the mucosa-associated bacteria that interact more directly with your intestinal cells. The duodenal microbiota shows higher diversity and different dominant species than what appears in stool.

The lactulose breath test detects small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which affects approximately 30-40% of IBS patients. This test measures hydrogen and methane production after you consume lactulose, indicating bacterial fermentation where it shouldn’t occur in high amounts.

Blood tests, imaging, and colonoscopy help rule out inflammatory bowel disease, infections, or structural problems but don’t diagnose dysbiosis itself.

Dietary and Lifestyle Strategies

The low FODMAP diet restricts fermentable carbohydrates that feed gut bacteria, reducing gas production and osmotic effects that trigger IBS symptoms. Research shows 50-70% of IBS patients experience symptom improvement, though this approach doesn’t correct the underlying dysbiosis.

FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. You eliminate high-FODMAP foods for 2-6 weeks, then systematically reintroduce them to identify your specific triggers.

The diet works by temporarily starving problematic bacteria, but long-term restriction can reduce beneficial Bifidobacterium populations. You should work with a dietitian to ensure adequate fiber intake and prevent further microbiome depletion.

Identifying food intolerances helps many patients, though true intolerances differ from FODMAP sensitivity. Lactose, fructose, and histamine intolerances result from enzyme deficiencies or dysbiosis-related issues rather than immune responses.

Stress management directly affects your gut microbiome through the brain-gut-microbiome axis, though dietary changes typically provide more immediate symptom relief.

Use of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Antibiotics

Probiotics show inconsistent results in IBS treatment because different strains produce different effects. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species generally help IBS-D patients, while some strains worsen gas and bloating in others.

Lactobacillus rhamnosus specifically prevents increased intestinal permeability in IBS patients, which explains why some probiotic treatment protocols reduce symptoms while others fail. You need strain-specific products with adequate colony-forming units (typically 10-20 billion CFU), not generic formulations.

Good bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids that maintain your intestinal barrier, regulate immune function, and reduce inflammation. IBS-C patients show lower SCFA levels than those with IBS-D or IBS-U, suggesting different bacterial populations require different interventions.

Prebiotics feed beneficial bacteria but frequently worsen symptoms during active flares. Inulin, fructooligosaccharides, and galactooligosaccharides increase Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus populations when tolerated. Starting with very low doses (2-3 grams daily) prevents the gas and bloating that cause most patients to discontinue them.

Rifaximin, a non-absorbable antibiotic, treats SIBO and IBS-D effectively by reducing bacterial overgrowth. Treating SIBO requires 10-14 days of rifaximin, which increases Faecalibacterium prausnitzii levels—a beneficial species reduced in IBS-M patients. The antibiotic paradoxically improves microbiome balance by eliminating pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae while preserving anaerobic beneficial species.

Medical and Integrative Interventions

Medications target specific IBS symptoms rather than dysbiosis directly. Antispasmodics reduce cramping, laxatives address constipation, and antidiarrheals slow transit time. These provide symptom relief but don’t restore microbial balance.

Gut-directed hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy address the brain-gut-microbiome axis dysfunction. The vagus nerve connects your gut microbiota to your central nervous system, which explains why psychological interventions produce measurable changes in gut function and microbiome composition.

Fecal microbiota transplantation remains experimental for IBS, with mixed results in clinical trials. The procedure works better for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections than functional disorders, possibly because IBS involves complex host-microbe interactions beyond simple bacterial replacement.

A stool test before starting treatment helps identify specific imbalances, though insurance rarely covers comprehensive microbiome analysis. Standard tests may show pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella or parasites but miss subtle dysbiosis patterns.

You should consult a gastroenterologist if symptoms persist despite dietary changes, if you experience unintended weight loss, or if you see blood in your stool—these indicate potential conditions beyond simple IBS or dysbiosis.

This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a qualified healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment recommendations specific to your condition.