You might not think much about how you sit at your desk or slouch on the couch after meals, but your posture could be quietly interfering with your digestive system. Poor posture can affect digestion by compressing abdominal organs, increasing pressure on the stomach, and disrupting the normal movement of food through your digestive tract. When you hunch forward or slouch, you’re literally squeezing the space your organs need to function properly.

The connection between your spine alignment and your gut isn’t just theoretical. Slouching can trigger heartburn, slow down how quickly food moves through your intestines, and even contribute to issues like constipation and bloating. Your diaphragm, which sits just above your stomach and plays a role in digestive function, can’t work optimally when you’re compressed into a poor position.

Understanding how your daily postural habits affect your digestive comfort can help you make simple changes that lead to noticeable improvements. This article examines the specific mechanisms linking posture to digestion, identifies which digestive issues are most affected by alignment problems, and provides practical strategies for supporting both your spine and your gut health.

Medical Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. If you experience persistent digestive symptoms, consult with a healthcare provider for proper diagnosis and treatment.

How Poor Posture Affects Digestion

Poor posture creates physical compression of your digestive organs, disrupts the natural wavelike movements that push food through your system, and weakens the valve that prevents stomach acid from flowing backward into your esophagus.

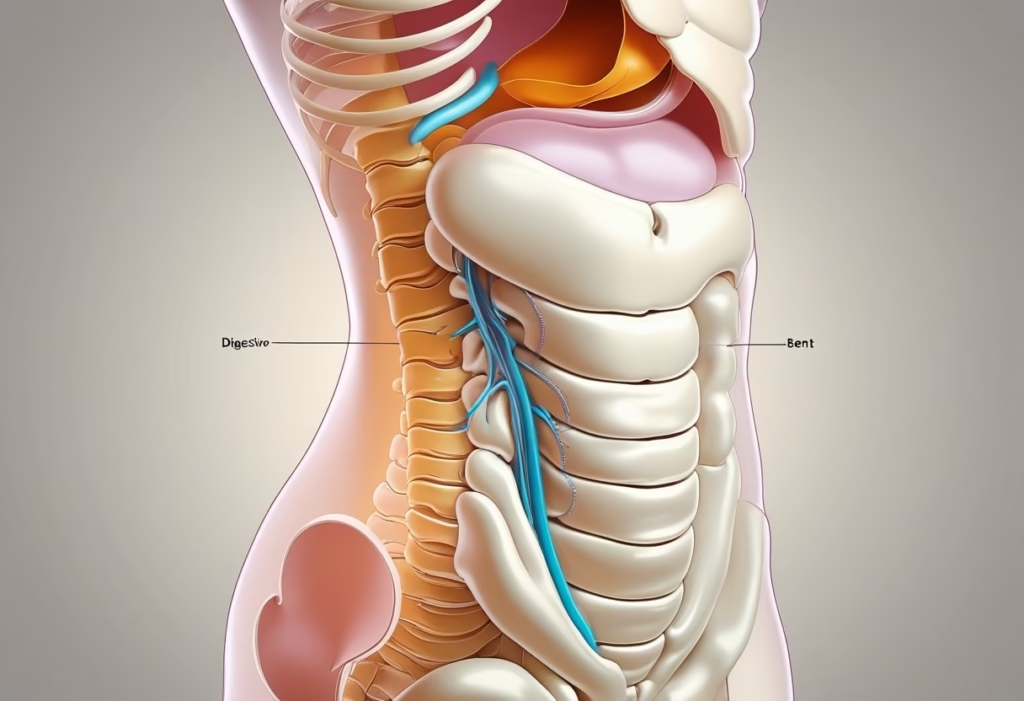

Compression of Abdominal Organs

When you slouch or hunch forward, your ribcage moves closer to your pelvis. This reduces the space available for your stomach, intestines, and other abdominal organs by up to 30%.

Your stomach needs room to expand as it fills with food and churns it with digestive acids. Compressed positioning forces your stomach into an unnatural shape, which slows the breakdown of food. This explains why you might feel uncomfortably full after eating smaller portions when sitting with poor posture.

The compression also affects your intestines. Your small intestine needs space to perform peristaltic contractions efficiently. When squeezed, these organs struggle to maintain proper function, leading to delayed gastric emptying. Studies show that sustained forward-leaning positions can increase abdominal pressure significantly, restricting blood flow to digestive organs.

This reduced blood flow matters because your digestive system requires adequate circulation to absorb nutrients and remove waste products. The combination of physical compression and reduced circulation creates a cascade effect that impairs multiple digestive processes simultaneously.

Impact on Gut Motility and Peristalsis

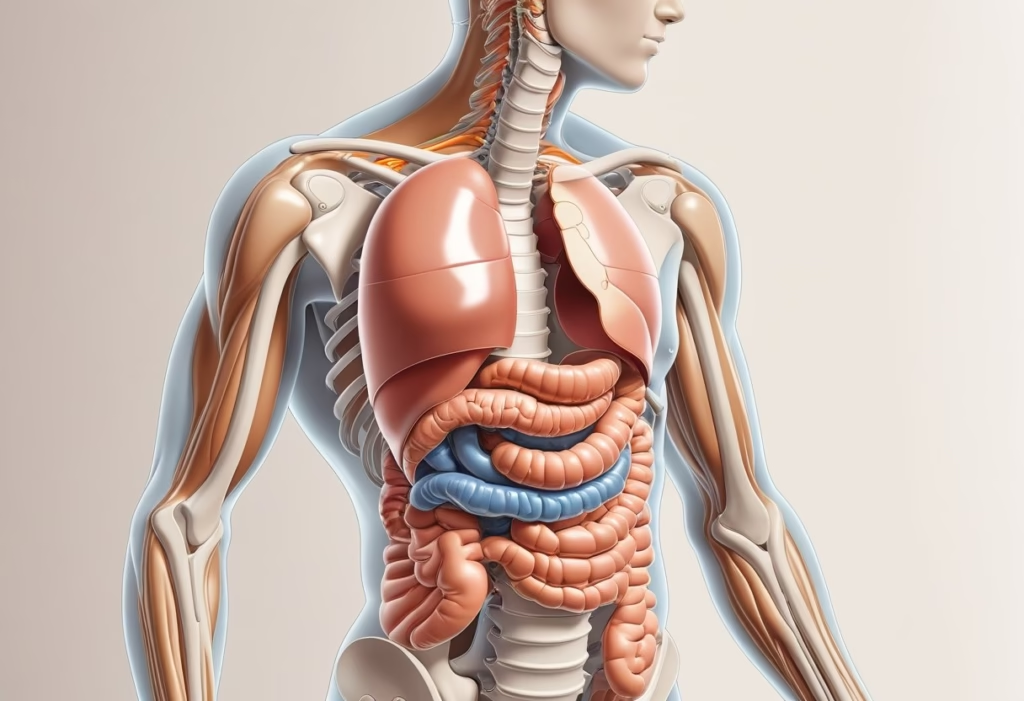

Peristalsis is the coordinated muscle contraction that moves food through your digestive tract. Your posture directly influences how effectively these contractions occur.

Slouching weakens your core muscles and disrupts spinal alignment. This affects the autonomic nervous system signals that control peristalsis. When your spine deviates from a neutral position, nerve signals traveling from your spinal cord to your digestive organs can become less efficient.

Research indicates that maintaining a neutral spine supports optimal gut motility. Poor posture creates tension in your abdominal wall, which interferes with the natural rhythm of peristaltic waves. This results in slow digestion, where food sits longer in your stomach and moves sluggishly through your intestines.

The mechanical pressure from slouching also reduces the amplitude of peristaltic contractions. Weaker contractions mean food doesn’t move as effectively, increasing your risk of constipation and bloating. You’ll typically notice these symptoms worsen after meals when sitting hunched over a desk or computer for extended periods.

Effects on Lower Esophageal Sphincter

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is a ring of muscle at the bottom of your esophagus that acts as a one-way valve. It opens to let food into your stomach and closes to prevent stomach acid from backing up.

Slouching increases intra-abdominal pressure, which pushes against your stomach and forces its contents upward. This pressure can overwhelm the LES, causing it to open when it should remain closed. The result is acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms.

A hunched posture also changes the angle between your esophagus and stomach, known as the angle of His. This angle normally helps prevent reflux. When you slouch, this angle becomes less acute, making it easier for stomach acid to escape into your esophagus.

Studies show that people who maintain poor posture after eating experience reflux symptoms 70% more frequently than those who sit upright. The symptoms typically worsen when you lean forward while sitting or immediately lie down after meals. Maintaining proper spinal alignment helps preserve the natural pressure gradient that keeps your LES functioning correctly.

Digestive Issues Linked to Poor Posture

Slouching and hunching compress your abdominal cavity, which directly interferes with how your digestive organs function. This compression can trigger or worsen conditions like constipation, acid reflux, bloating, and irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.

Constipation and Bowel Irregularity

When you sit or stand with poor posture, you compress your intestines and reduce the space they need to contract properly. This compression slows peristalsis, the wave-like muscle contractions that move waste through your digestive tract.

Slouching also affects your diaphragm’s movement, which normally assists in pushing food through your system. When the diaphragm can’t expand fully, it reduces the natural massage effect that helps stimulate bowel movements.

The angle at which you sit matters significantly. Leaning forward or curling your spine creates a kink in your colon, making it harder for stool to pass through. This mechanical obstruction forces your intestines to work harder, often resulting in incomplete evacuation.

If you experience constipation that lasts more than three weeks alongside postural changes, consult a gastroenterologist to rule out other conditions.

Acid Reflux and Heartburn

Poor posture weakens the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the muscle valve that prevents stomach acid from flowing backward into your esophagus. Slouching increases abdominal pressure, which pushes stomach contents upward against this valve.

Hunching forward after meals is particularly problematic. This position compresses your stomach while simultaneously reducing the angle between your esophagus and stomach, making it easier for acid to escape.

Studies show that maintaining an upright posture for at least two hours after eating reduces gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms by up to 40%. Sitting at a 90-degree angle or standing provides the gravitational assistance your digestive system needs.

Common mistake: Lying down or reclining immediately after eating while slouched creates the worst possible scenario for acid reflux. If symptoms occur more than twice weekly or interfere with sleep, see a doctor, as chronic GERD can damage your esophageal lining.

Bloating and Gas

Compressed abdominal organs from slouching trap gas in your intestines rather than allowing it to move through naturally. Your digestive tract needs room to expand and contract during the digestive process.

Poor posture slows gastric emptying, meaning food sits in your stomach longer than it should. This extended retention time increases fermentation by gut bacteria, producing excess gas. The compressed position also makes it harder for gas to travel through your intestinal tract.

When you hunch over, you create pockets where gas accumulates instead of being expelled. Standing up straight opens these pathways and allows trapped gas to move more freely.

What helps: Walking for 10-15 minutes after meals while maintaining good posture can reduce bloating significantly. What rarely helps: Taking digestive enzymes without addressing the postural component, since the issue is mechanical rather than enzymatic.

Indigestion and IBS Symptoms

Slouching compresses your stomach, limiting its ability to churn food effectively and mix it with digestive enzymes. This incomplete mechanical breakdown leads to that heavy, uncomfortable feeling associated with indigestion.

For people with irritable bowel syndrome, poor posture amplifies existing symptoms. The compression increases intestinal sensitivity and can trigger the pain signals that characterize IBS. Tension in your neck and shoulders from poor posture also reduces vagal tone, which regulates gut motility and digestive enzyme secretion.

Research indicates that postural stress influences your gut-brain axis, potentially increasing cortisol levels that affect digestion. This creates a cycle where poor posture causes digestive discomfort, which then causes you to tense up and slouch more.

If you have IBS and notice symptoms worsen during long periods of sitting, your posture likely contributes to flare-ups. Seek medical evaluation if symptoms persist despite postural corrections, as other underlying conditions may require treatment.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for persistent or severe digestive symptoms.

Mechanisms Linking Posture and Digestive Health

Poor posture disrupts digestive function through physical compression of organs, altered pressure dynamics, impaired nerve signaling, and restricted breathing patterns. These mechanisms work together to slow gut motility, trigger reflux symptoms, and interfere with the body’s natural digestive processes.

Role of Core Muscles and Spinal Alignment

Your core muscles form a structural support system that maintains spinal alignment and protects your digestive organs. When these muscles weaken from prolonged sitting or slouching, your spine loses its natural curves and your ribcage collapses forward. This compression reduces the space available for your stomach, intestines, and other abdominal organs to function properly.

Weak core muscles also fail to stabilize your pelvis and lower back, creating a forward tilt that increases pressure on your digestive tract. You may notice this feels worse after meals when your stomach is full. The most common mistake people make is assuming they need intense ab workouts, when what actually helps is consistent engagement of deep stabilizing muscles like the transversus abdominis.

Strengthening these muscles through exercises like dead bugs, bird dogs, and planks allows your digestive organs to sit in their optimal positions. This matters because even slight misalignment can slow the movement of food through your intestines.

Influence of Intra-Abdominal Pressure

Intra-abdominal pressure refers to the force exerted within your abdominal cavity. When you slouch, this pressure increases unnaturally and pushes against your stomach and intestines. The result is that stomach contents get forced upward toward your esophagus, explaining why you experience more acid reflux when hunched over a desk or phone.

This elevated pressure also constricts blood flow to digestive tissues, reducing oxygen and nutrient delivery to the gut lining. Your intestines need adequate circulation to maintain their barrier function and absorb nutrients efficiently.

What makes this worse:

- Eating while slouched forward

- Wearing tight clothing around your waist

- Sitting immediately after large meals

- Chronic forward head posture

Standing or sitting upright normalizes this pressure distribution, allowing your lower esophageal sphincter to close properly and preventing backflow. If you experience bloating or reflux more than twice a week despite posture changes, you should see a gastroenterologist to rule out structural issues.

Vagus Nerve and Gut-Brain Axis

The vagus nerve connects your brainstem to your digestive organs, controlling everything from stomach acid secretion to intestinal contractions. When you maintain proper spinal alignment, this nerve transmits signals efficiently. But chronic slouching compresses the nerve pathway through your neck and thoracic spine, weakening these signals.

This compression directly impacts gut-brain axis communication. Your gut produces neurotransmitters like serotonin that influence mood and stress levels, while your brain sends signals that regulate digestion. Poor posture disrupts this bidirectional flow, which explains why people with chronic slouching often report both digestive complaints and increased anxiety.

The vagus nerve specifically controls peristalsis, the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through your intestines. Reduced vagal tone from postural compression slows this process, leading to constipation and bloating. Medical research has shown that vagus nerve stimulation improves gut motility, though you don’t need devices when postural correction naturally enhances nerve function.

Diaphragm Function and Breathing

Your diaphragm, the primary breathing muscle, sits directly above your digestive organs and plays a crucial role in digestive health. Proper diaphragmatic breathing creates a massaging effect on your stomach and intestines with each breath. When you slouch, your diaphragm cannot descend fully, forcing you into shallow chest breathing that eliminates this benefit.

This restricted movement prevents the natural rhythmic pressure changes that stimulate gut motility. You breathe roughly 20,000 times per day, meaning chronic shallow breathing represents 20,000 missed opportunities to support your digestion.

Breathing patterns that help:

- Deep belly breathing where your abdomen expands on inhale

- Exhaling fully to engage core muscles

- Breathing through your nose rather than mouth

Hunched posture also reduces lung capacity by up to 30%, decreasing oxygen delivery to all tissues including your gut. Lower oxygen levels impair the metabolic processes your intestinal cells need to absorb nutrients and maintain barrier integrity. If you notice digestive symptoms worsen during stressful periods when breathing becomes shallow, this mechanism is likely contributing.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Persistent digestive symptoms require evaluation by a qualified healthcare provider to rule out underlying conditions.

Risk Factors and Common Postural Habits

Certain daily behaviors and body positions create mechanical compression of the digestive organs, which directly interferes with normal gut function. Office workers, smartphone users, and people who remain seated after eating face the highest risk of posture-related digestive problems.

Slouching and Hunching Behaviors

When you slouch, your ribcage collapses toward your pelvis, reducing the space available for your stomach and intestines. This compression increases intra-abdominal pressure and physically restricts the muscular contractions your digestive system needs to move food through your gut.

What happens when you slouch:

- Your stomach gets squeezed, slowing the emptying process

- Gas becomes trapped more easily, causing bloating

- The lower esophageal sphincter experiences increased pressure, allowing acid to flow upward

Research published in the Journal of Gastroenterology found that people who slouch after eating experience a 35% increase in acid reflux symptoms compared to those maintaining upright posture. The compression also weakens your core muscles over time, which further reduces digestive efficiency since these muscles support proper organ positioning.

You’re most at risk if you spend hours hunched over a desk, lean forward while gaming, or collapse into a couch immediately after meals. The sustained compression prevents your intestines from contracting normally, leading to constipation and prolonged discomfort.

Forward Head Posture and Pelvic Tilt

Forward head posture occurs when your head juts forward past your shoulders, often from looking down at phones or computer screens. For every inch your head moves forward, you add 10 pounds of pressure to your spine, which cascades down to affect your abdominal cavity.

This misalignment typically pairs with anterior pelvic tilt, where your pelvis rotates forward and your lower back arches excessively. Together, these positions alter the natural curve of your spine and change how your organs sit in your abdomen.

The combination creates specific digestive problems. Your esophagus angles incorrectly, making reflux more likely. Your diaphragm can’t move properly during breathing, which affects the gentle massage your organs receive with each breath. Your intestines get pushed into awkward positions where peristalsis becomes less effective.

You’ll notice symptoms worsen during activities that reinforce these positions: driving long distances, working on a laptop without proper screen height, or scrolling through your phone for extended periods.

Prolonged Sitting and After-Meal Posture

Sitting for hours compresses your abdomen regardless of posture quality, but the position you hold immediately after eating matters most. When you eat and then sit hunched over, food sits in your stomach longer because gravity and compression work against the normal digestive flow.

Critical timing factors:

- Slouching within 30 minutes of eating significantly increases reflux risk

- Remaining seated for 2+ hours after large meals slows gastric emptying

- Lying down within 3 hours of eating allows acid to travel up your esophagus more easily

Office workers who eat lunch at their desks and immediately return to hunched computer work create ideal conditions for indigestion. The compression prevents your stomach from churning food effectively and restricts blood flow to digestive organs.

An ergonomic chair with lumbar support helps maintain spinal curves, but it doesn’t eliminate compression entirely. A standing desk allows you to alternate positions and reduce abdominal pressure, though standing immediately after eating can sometimes worsen symptoms in people with certain digestive conditions. The key is maintaining an upright trunk position for at least 30 minutes post-meal, whether sitting or standing, before gradually returning to normal activities.

Improving Posture to Support Digestive Health

Correcting postural alignment requires changes to your workspace setup, targeted physical exercises that strengthen supporting muscles, and sometimes professional guidance to address deeply ingrained movement patterns. These interventions work by reducing compression on digestive organs and restoring proper nerve signaling to the gut.

Ergonomics and Daily Habits

Your workspace setup directly determines how much pressure you place on your abdominal organs during the 8-10 hours you spend sitting each day. Position your computer monitor at eye level so you don’t crane your neck forward, which creates a chain reaction of spinal compression down to your abdomen.

Choose a chair with adjustable lumbar support that maintains the natural curve of your lower back. Your feet should rest flat on the floor with knees at a 90-degree angle. This position prevents the slumping that compresses your stomach and intestines against your diaphragm.

Set a timer to stand every 30-40 minutes because sustained sitting reduces gut motility regardless of your posture quality. When standing, distribute your weight evenly between both feet rather than shifting to one hip, which twists the abdominal cavity.

A common mistake is tucking your pelvis under while sitting, which many people do thinking it improves posture. This actually increases abdominal compression and can worsen symptoms like bloating and acid reflux.

Core Strengthening and Postural Exercises

Weak core muscles cannot maintain proper spinal alignment, forcing you to compensate with slouching positions that compress digestive organs. Planks build the deep abdominal and back muscles needed to hold your torso upright without strain. Hold a plank for 20-30 seconds, focusing on keeping your spine neutral rather than letting your hips sag or pike upward.

Pilates exercises specifically target the transverse abdominis and multifidus muscles that stabilize your spine and create space for your organs. Studies show that 8 weeks of Pilates training improves both posture and reduces gastrointestinal symptoms in people with chronic digestive issues.

Avoid crunches and sit-ups as your primary core exercises because they reinforce the forward-hunched position that restricts digestion. Bird dogs and dead bugs better train your core to support upright posture.

Professional Support and Therapy

A physical therapist can identify specific muscle imbalances causing your poor posture. They assess which muscles are overly tight (often chest and hip flexors) versus weak (typically upper back and glutes), then design corrective exercises addressing your individual pattern.

Chiropractors provide spinal adjustments that may offer temporary relief from postural discomfort, but research shows lasting improvement requires the strengthening exercises that physical therapists emphasize. Some people benefit from combining both approaches.

See a healthcare provider if you experience persistent digestive symptoms despite posture corrections after 4-6 weeks. Chronic bloating, reflux, or constipation may indicate underlying conditions requiring medical treatment beyond postural changes.

Benefits of Good Posture on Gut Health

Proper spinal alignment creates space for your digestive organs to function without compression, allowing smoother food transit and reducing the physical stress that triggers common gut problems. This positioning also supports better breathing patterns that directly influence digestive efficiency.

Optimized Digestion and Nutrient Absorption

When you sit or stand upright, your digestive organs maintain their natural positions without compression. This allows your stomach to produce gastric acid efficiently and your intestines to contract rhythmically during peristalsis.

Good posture enables your diaphragm to move freely during breathing. Each breath provides a gentle massage to your digestive organs, promoting blood circulation. Enhanced blood flow delivers oxygen and nutrients that your gut cells need for optimal enzyme production and nutrient absorption.

The mechanical advantage matters significantly. Your esophagus functions best when aligned vertically, reducing the likelihood of stomach acid traveling upward. Your intestines also benefit from proper spacing, allowing waste to move through more efficiently.

Research indicates that postural alignment affects the vagus nerve, which controls digestive processes including stomach acid secretion and intestinal motility. When your spine is properly aligned, this nerve can transmit signals more effectively between your brain and gut.

Reduction in Digestive Discomforts

Maintaining proper posture reduces pressure on your abdominal cavity. This decrease in compression alleviates symptoms like bloating, gas, and the feeling of fullness after meals.

Common improvements include:

- Less acid reflux and heartburn

- Reduced bloating after eating

- Fewer episodes of trapped gas

- Decreased abdominal cramping

Slouching compresses your stomach and can force acid into your esophagus. When you sit upright, gravity helps keep stomach contents where they belong. This is why eating while hunched over your phone often worsens reflux symptoms.

Good posture also prevents the kinking of your intestines that can slow transit time. When waste moves at a normal pace, you’re less likely to experience constipation or the bacterial overgrowth that causes excessive gas production.

Long-Term Digestive Wellness

Consistent postural habits influence bowel regularity over time. Your intestines adapt to the space and positioning you provide them, establishing patterns that either support or hinder digestive health.

Proper alignment reduces chronic inflammation in your gut. When organs aren’t constantly compressed, the physical stress on tissues decreases. This matters because mechanical stress can trigger inflammatory responses that affect gut permeability and overall digestive function.

Your posture affects how effectively your body eliminates waste. Regular bowel movements prevent toxin buildup and maintain a healthier gut microbiome. When waste stagnates due to postural compression, it can alter bacterial balance and contribute to conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

The cumulative effect of good posture includes better overall gut-brain communication. This connection regulates digestive enzyme release, intestinal contractions, and even your gut’s immune response.

Medical Note: While improving posture can alleviate many digestive symptoms, persistent issues like chronic constipation, severe bloating, or acid reflux lasting beyond a few weeks warrant medical evaluation to rule out underlying conditions.