Your gut health depends on both digestive enzymes and probiotics, but they work in completely different ways and address distinct digestive issues. Digestive enzymes are proteins that break down food into absorbable nutrients, while probiotics are living microorganisms that balance your gut bacteria and support immune function. Understanding which one you need requires looking at your specific symptoms and digestive challenges.

Many people assume these supplements are interchangeable or that one is superior to the other. The reality is that digestive enzymes help with immediate food breakdown, making them useful for bloating and gas after meals, while probiotics work over weeks to months to reshape your microbiome and may help with issues like diarrhea or constipation. You might benefit from one, both, or neither depending on what’s actually causing your digestive discomfort.

This guide explains the mechanisms behind each supplement, the specific conditions they address, and the common mistakes people make when choosing between them. You’ll learn when enzyme deficiencies occur, how probiotics actually colonize your gut, and whether combining both supplements provides additional benefits. This information is for educational purposes and does not replace medical advice from a qualified healthcare provider, especially if you have persistent digestive symptoms or diagnosed conditions.

Digestive Enzymes vs. Probiotics: Key Differences

Digestive enzymes and probiotics support digestion through fundamentally different mechanisms, with enzymes acting as chemical catalysts and probiotics functioning as living organisms that reshape your gut environment.

How Each Supports Digestion

Digestive enzymes are non-living proteins that accelerate the breakdown of food molecules. Your body produces three main types: amylase in your saliva breaks down carbohydrates into simple sugars, protease in your stomach splits proteins into amino acids, and lipase from your pancreas converts fats into fatty acids. These enzymes work immediately when they contact food, functioning like chemical scissors that cut large molecules into smaller pieces your intestines can absorb.

Probiotics are living bacteria and yeasts that balance your gut microbiome. They don’t directly break down food. Instead, they create an environment where digestion happens more efficiently by crowding out harmful bacteria, producing short-chain fatty acids that support your gut lining, and influencing how your body processes nutrients.

The key distinction: enzymes handle the mechanical process of breaking down what you eat, while probiotics manage the ecosystem where this breakdown occurs. You can have adequate enzyme production but still experience digestive problems if your gut bacteria are imbalanced, and vice versa.

Immediate Relief vs. Long-Term Balance

Digestive enzymes typically provide faster relief for acute symptoms. If you take them 15-30 minutes before eating a meal high in fat, protein, or carbohydrates, they start working as soon as food enters your digestive tract. You might notice reduced bloating and that heavy feeling within 30-60 minutes after eating.

However, enzymes only work while they’re in your system. Once they’ve been used up or eliminated, their effects stop. This makes them useful for situational needs—like taking lactase before consuming dairy if you’re lactose intolerant, or adding a broad-spectrum enzyme when eating a particularly rich meal.

Probiotics require patience. It takes 2-4 weeks of consistent daily use before most people notice improvements in gut health. Clinical studies show that probiotics need time to colonize your digestive tract, compete with existing bacteria, and establish themselves in sufficient numbers to make a difference.

The trade-off is durability. While enzymes offer immediate but temporary support, probiotics create lasting changes to your gut environment that continue benefiting you even between doses.

Choosing Based on Symptoms

You likely need digestive enzymes if you experience:

- Feeling uncomfortably full for hours after normal-sized meals

- Frequent burping or belching shortly after eating

- Undigested food visible in your stool

- Symptoms that worsen with fatty or protein-heavy foods

- A “brick in your stomach” sensation

These symptoms suggest your body isn’t producing enough enzymes to properly break down food. People over 50, those with pancreatic conditions, or anyone with chronic acid reflux often fall into this category.

You likely need probiotics if you experience:

- Irregular bowel movements (constipation alternating with diarrhea)

- Bloating that builds throughout the day regardless of meals

- Digestive problems that started after antibiotics

- Skin issues like acne or eczema alongside digestive complaints

- Frequent infections or weakened immunity

Understanding these differences helps you avoid common mistakes. Taking probiotics for immediate pre-meal relief rarely helps because they don’t work that way. Similarly, expecting enzymes to fix chronic dysbiosis won’t address the underlying bacterial imbalance.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before starting any supplement, especially if you have pancreatic disorders, diabetes, or take prescription medications.

How Digestive Enzymes Work

Digestive enzymes are proteins produced primarily in your pancreas, stomach, and small intestine that break down macronutrients into molecules small enough for your body to absorb. Without adequate enzyme activity, food passes through your digestive tract incompletely digested, leading to malabsorption and uncomfortable symptoms.

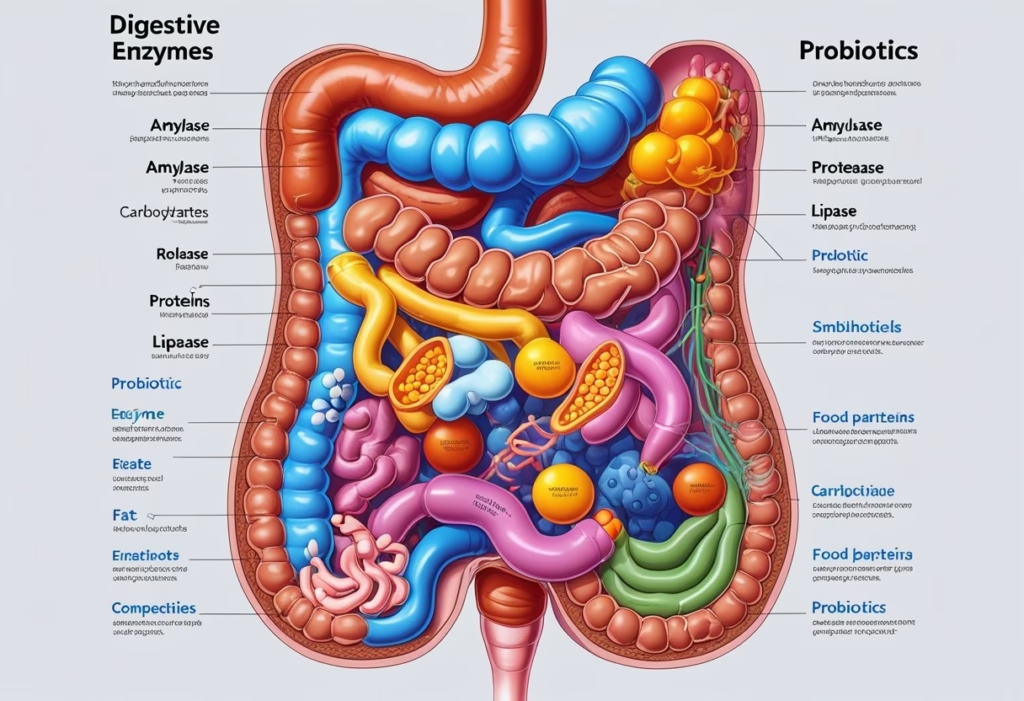

Types of Digestive Enzymes

Your body produces specific enzymes for each type of macronutrient. Amylase breaks down carbohydrates and starches into simple sugars, beginning in your mouth and continuing in your small intestine. Protease splits proteins into amino acids, which is essential for building and repairing tissues throughout your body.

Lipase breaks down fats into fatty acids and glycerol. This enzyme is particularly important because fat malabsorption leads to greasy, floating stools and deficiencies in fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

Lactase specifically breaks down lactose, the sugar in dairy products. People with lactose intolerance lack sufficient lactase, which is why dairy causes them bloating and diarrhea. Bromelain from pineapple and papain from papaya are plant-based proteases that can aid protein digestion when consumed with meals.

Alpha-galactosidase breaks down complex carbohydrates in beans, cruciferous vegetables, and whole grains. Without it, these foods reach your colon undigested, where bacteria ferment them and produce excessive gas.

Benefits of Digestive Enzymes

Digestive enzymes help reduce bloating, gas, and digestive discomfort by ensuring complete food breakdown before it reaches your colon. When food is properly digested in your small intestine, you avoid the fermentation that causes these symptoms.

Digestive enzyme supplements help with nutrient absorption, which matters if you have pancreatic insufficiency or other conditions affecting enzyme production. Better absorption means you extract more vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients from the food you eat.

For people with food intolerances related to enzyme deficiencies, supplementation provides immediate digestive support. Taking lactase before consuming dairy or alpha-galactosidase before eating beans prevents symptoms rather than treating them after they occur. This differs from general dietary changes because it addresses the specific biochemical problem preventing proper digestion.

Signs of Enzyme Deficiency

Persistent bloating within 30 minutes to 2 hours after meals suggests your body isn’t breaking down food efficiently. The timing matters—immediate bloating points to enzyme issues, while bloating 6-8 hours later typically indicates bacterial imbalances.

Undigested food particles in your stool, oily or greasy stools that float, and stools that are difficult to flush indicate fat malabsorption from lipase deficiency. Chronic diarrhea following meals, especially after eating fatty foods, is another red flag for enzyme deficiency.

Unexplained weight loss despite eating normally signals malabsorption. Your body cannot extract calories and nutrients from food if enzymes aren’t breaking it down properly. Conditions like IBS, chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, and celiac disease commonly cause enzyme deficiency.

You should see a doctor if you experience persistent digestive symptoms lasting more than two weeks, unexplained weight loss, bloody stools, severe abdominal pain, or jaundice. These symptoms may indicate pancreatic insufficiency or other serious conditions requiring prescription pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) rather than over-the-counter supplements.

Supplementation and Food Sources

Digestive enzyme supplements work best when taken immediately before or with your first bite of food. Taking them too early or too late reduces their effectiveness because they need to be present when food enters your digestive tract. The common mistake is taking enzymes on an empty stomach or hours after eating.

Enzyme-rich foods provide natural digestive support:

- Pineapple contains bromelain (protein digestion)

- Papaya contains papain (protein digestion)

- Mango contains amylase (carbohydrate digestion)

- Honey contains diastase and invertase (sugar digestion)

- Fermented foods like sauerkraut and kimchi contain various enzymes

Raw or minimally processed versions of these foods contain more active enzymes because heat above 118°F destroys enzyme activity. This is why cooked pineapple doesn’t provide the same digestive benefits as fresh pineapple.

Understanding the difference between digestive enzymes and probiotics helps you choose appropriate supplementation. Broad-spectrum enzyme formulas containing amylase, protease, and lipase address general digestive issues, while targeted supplements like lactase work for specific intolerances.

What usually helps: Taking enzymes with every meal containing the problematic nutrient, starting with lower doses and increasing as needed, and combining enzyme supplementation with smaller, more frequent meals.

What rarely helps: Taking random enzyme supplements without matching them to your symptoms, relying solely on enzyme-rich foods for significant deficiencies, or expecting enzymes to fix problems caused by bacterial overgrowth or motility disorders.

This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement regimen, especially if you have a diagnosed digestive condition or take medications.

How Probiotics Benefit Gut Health

Probiotics are living microorganisms that support your digestive system by maintaining microbiome balance, producing beneficial compounds, strengthening your intestinal barrier, and modulating immune responses. Different strains of bacteria and yeast offer distinct benefits, and you can obtain them through both fermented foods and targeted supplements.

Probiotic Strains and Their Roles

Not all probiotics work the same way. Each strain has specific functions backed by clinical research.

Lactobacillus strains are among the most studied probiotic microbes. These bacteria naturally inhabit your small intestine and vaginal tract. Certain lactobacillus strains produce lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose, which explains why they may help if you experience digestive discomfort from dairy. Other strains produce lactic acid, which creates an inhospitable environment for harmful bacteria.

Bifidobacterium species predominantly colonize your large intestine. These beneficial microbes ferment dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, which nourish the cells lining your colon. Research shows bifidobacterium strains may support gut barrier function and immune health.

Saccharomyces boulardii is a beneficial yeast, not a bacteria. This probiotic has been studied for its ability to survive stomach acid and antibiotics, making it particularly useful during or after antibiotic treatment when your bacterial balance is disrupted.

The potency of probiotic supplements is measured in CFU (colony-forming units). However, a higher CFU count doesn’t automatically mean better results. Strain specificity matters more than quantity.

Impact on the Gut Microbiome

Your gut microbiome contains trillions of microorganisms that influence digestion, metabolism, and immune function. Probiotics don’t permanently colonize your gut, but they influence your gut environment as they pass through.

When you take probiotics regularly, they interact with your existing gut flora. This interaction can increase microbiome diversity, which research associates with better health outcomes. A diverse microbiome is more resilient against disruptions from stress, poor diet, or medications.

Probiotics help maintain microbiome balance by competing with potentially harmful bacteria for nutrients and attachment sites in your intestinal lining. They also produce antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of unwanted microbes.

One common mistake is expecting immediate results. Unlike digestive enzymes that work within hours, probiotics typically require 2-4 weeks of consistent daily use before you notice changes. Stopping too soon means you won’t experience their full effects.

Immune and Barrier Support

About 70% of your immune system resides in your gut. Probiotics communicate with immune cells in your intestinal lining, helping to modulate immune responses.

Your gut barrier is a single layer of cells that separates your bloodstream from the contents of your intestines. When this barrier weakens, partially digested food particles and bacteria can trigger inflammation. Certain probiotic strains strengthen the tight junctions between these cells, reinforcing the barrier.

Beneficial microbes also produce metabolites that support immune health. For example, some strains generate compounds that promote the development of regulatory immune cells, which help prevent overactive immune responses.

If you experience persistent digestive symptoms despite taking probiotics, or if you develop new symptoms like severe abdominal pain, fever, or bloody stools, see a doctor. These could indicate conditions requiring medical treatment beyond probiotic supplementation.

Probiotic Foods and Supplements

You can obtain probiotics through fermented foods or supplements. Each option has distinct advantages.

Fermented foods provide probiotics along with nutrients and other beneficial compounds:

- Yogurt contains lactobacillus and bifidobacterium strains when labeled with “live active cultures”

- Kefir offers a wider variety of bacterial strains and beneficial yeasts than yogurt

- Kimchi and sauerkraut provide probiotics plus prebiotic fiber from vegetables

- Miso and tempeh deliver probiotics alongside protein and fermented soy nutrients

- Kombucha contains bacteria and yeast, though sugar content varies by brand

The main limitation of fermented foods is inconsistent CFU counts and strain identification. You don’t know exactly which strains or how many live microbes you’re getting.

Probiotic supplements offer standardized doses of specific, clinically-studied strains. Look for products that list complete strain names, not just genus and species. Quality supplements use protective delivery systems to help bacteria survive stomach acid.

A common mistake is storing probiotics incorrectly. Many require refrigeration to maintain viability. Heat, moisture, and light degrade living microbes, reducing their effectiveness.

This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before starting any supplement regimen, especially if you have a compromised immune system or serious health condition.

Comparing Applications: When to Use Digestive Enzymes or Probiotics

Digestive enzymes work immediately to break down specific food components during meals, while probiotics influence your gut ecosystem over weeks to months. Your symptoms, their timing, and underlying conditions determine which supplement addresses your specific needs.

Bloating, Gas, and Digestive Discomfort

If you experience bloating and gas within 30 minutes to 2 hours after eating, digestive enzymes typically provide faster relief. This timing indicates incomplete food breakdown in your upper digestive tract.

Digestive enzymes help when:

- Bloating occurs predictably after high-fat, high-protein, or high-carb meals

- You notice undigested food in your stool

- Symptoms appear immediately after eating specific foods

- You have functional dyspepsia with meal-related discomfort

- Age-related enzyme decline affects digestion

Probiotics address:

- Persistent bloating unrelated to specific meals

- Gas from bacterial fermentation in your lower digestive tract

- Burping and digestive discomfort linked to gut bacterial imbalance

- Symptoms that develop 4-6 hours after eating

The common mistake is taking enzymes for fermentation-related gas. If your bloating worsens throughout the day rather than immediately after meals, your gut microbiome likely needs attention. Probiotics take 2-4 weeks to show effects, so immediate symptom relief suggests you needed enzymes instead.

Digestive Disorders and Food Intolerances

Your diagnosis determines which supplement provides therapeutic benefit. Digestive enzymes support conditions where your body produces insufficient enzymes, while probiotics help when gut barrier function or microbial balance is compromised.

Conditions requiring digestive enzymes:

- Pancreatitis: Pancreatic insufficiency prevents adequate lipase production

- Lactose intolerance: Missing lactase enzyme causes dairy-related symptoms

- Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency: Fat malabsorption requires prescription-strength lipase

- Cystic fibrosis: Thick mucus blocks enzyme delivery

Conditions benefiting from probiotics:

- IBS: Specific strains reduce pain, diarrhea, and constipation

- Inflammatory bowel disease: Certain strains support remission maintenance

- Leaky gut concerns: Probiotics strengthen intestinal barrier function

- Antibiotic-associated diarrhea: Live cultures prevent microbiome disruption

Inflammatory bowel disease patients should consult gastroenterologists before starting probiotics, as some strains may trigger flares. Food sensitivities differ from intolerances—if you react to foods without enzyme deficiency, you may have autoimmune conditions requiring medical evaluation rather than supplements.

Weight Management and Overall Wellbeing

Neither supplement directly causes weight loss, but both influence factors affecting weight management through different mechanisms. Enzymes improve nutrient absorption from meals you already eat. Probiotics may affect metabolism, inflammation, and gut barrier integrity over extended periods.

Digestive enzymes support:

- Better nutrient extraction when malabsorption limits energy availability

- Reduced post-meal discomfort that interferes with regular eating patterns

- Improved digestion during dietary changes

Probiotics influence:

- Metabolic pathways through short-chain fatty acid production

- Systemic inflammation linked to metabolic health

- Gut barrier function that affects immune responses

The mistake is expecting either supplement to compensate for poor dietary choices. Weight management requires comprehensive lifestyle changes, not supplementation alone. Some research suggests specific probiotic strains may support metabolic health, but results vary significantly between individuals.

Medical Disclaimer: Consult your healthcare provider before starting digestive enzymes or probiotics, especially if you have pancreatitis, inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune conditions, or take medications. Persistent digestive symptoms lasting over two weeks require medical evaluation to rule out serious conditions.

Can Digestive Enzymes and Probiotics Be Taken Together?

Taking both supplements together is safe for most people and addresses different digestive needs simultaneously. Digestive enzymes work in the upper digestive tract to break down food, while probiotics colonize the lower intestine to balance gut bacteria and support your microbiome.

Potential Benefits of Combined Use

When you take digestive enzymes, they break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in your stomach and small intestine. This process prevents undigested food particles from reaching your colon, where they would ferment and cause bloating and gas.

Probiotics work to maintain gut flora balance in your large intestine, producing beneficial compounds like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including butyrate. These SCFAs feed your intestinal cells and reduce inflammation.

The combination helps because enzymes clear partially digested food before it reaches the colon, creating a better environment for probiotics to thrive. Without proper breakdown of food upstream, you risk feeding harmful bacteria instead of beneficial ones, potentially worsening dysbiosis. This explains why some people notice reduced digestive discomfort when using both supplements rather than just one.

Studies show that enzyme and probiotic supplementation can enhance intestinal barrier function, which helps prevent unwanted substances from entering your bloodstream.

Timing and Dosage Guidance

You should take digestive enzymes immediately before or with your first bite of food. This timing ensures the enzymes are present when food enters your stomach, maximizing their ability to support digestion.

Take probiotics on an empty stomach, ideally 30 minutes before meals or at bedtime. This approach minimizes exposure to stomach acid, allowing more beneficial bacteria to survive and reach your intestines where they colonize.

A common mistake is taking both supplements at the exact same time with food. While enzymes won’t destroy probiotic bacteria, taking them separately optimizes each supplement’s effectiveness. Some combination products are formulated to be taken together, so check your specific product label.

For a digestive enzyme supplement, look for broad-spectrum formulas containing amylase, protease, and lipase. Probiotic dosages typically range from 10 to 50 billion CFUs with multiple strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species.

Safety Considerations

Most people can safely combine these supplements without adverse effects. You might experience mild gas or changes in bowel movements during the first week as your digestive system adjusts to increased enzymatic activity and shifting bacterial populations.

See a doctor before starting if you have pancreatitis, digestive bleeding, or severe inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive enzymes can theoretically worsen inflammation in active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis flares.

People taking blood thinners should consult their physician, as some enzyme formulas contain bromelain or papain that may affect clotting. Immunocompromised individuals should avoid probiotics or use them only under medical supervision due to rare infection risks.

What rarely helps: taking excessive amounts thinking more is better. High enzyme doses can cause diarrhea, while excessive probiotics may trigger bloating. Start with recommended doses and adjust based on your response.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider before starting new supplements, especially if you have existing medical conditions or take medications.