Body odor doesn’t just come from what’s happening on your skin. Your gut bacteria produce odorous compounds during digestion that can enter your bloodstream and eventually be released through your breath, sweat, and urine, creating distinctive smells that regular showering won’t eliminate.

Many people struggle with persistent body odor despite excellent hygiene practices. They shower multiple times daily, use strong deodorants, and brush their teeth frequently, yet the smell returns within hours. The reason often lies in how gut bacteria metabolize food and produce volatile compounds like trimethylamine, hydrogen sulfide, and ammonia that travel from your digestive system throughout your body.

Understanding the connection between your digestive system and body odor helps explain why dietary changes, certain health conditions, and gut imbalances affect how you smell. This article examines the specific bacterial processes that generate odorous molecules, which body sites are most affected, and evidence-based approaches to managing gut-related odor issues. Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and doesn’t replace professional medical advice from your healthcare provider.

How Gut Bacteria Impact Body Odor

Gut bacteria produce volatile compounds that enter your bloodstream and exit through your breath, sweat, and urine. The types of bacteria in your gut microbiome determine which odorous molecules accumulate in your body.

Metabolic Pathways Producing Odorants

Your gut bacteria break down proteins and other nutrients to create volatile organic compounds that cause body odor. When you eat foods containing sulfur-containing amino acids like methionine and cysteine, certain bacterial species convert these into volatile sulfur compounds including hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol.

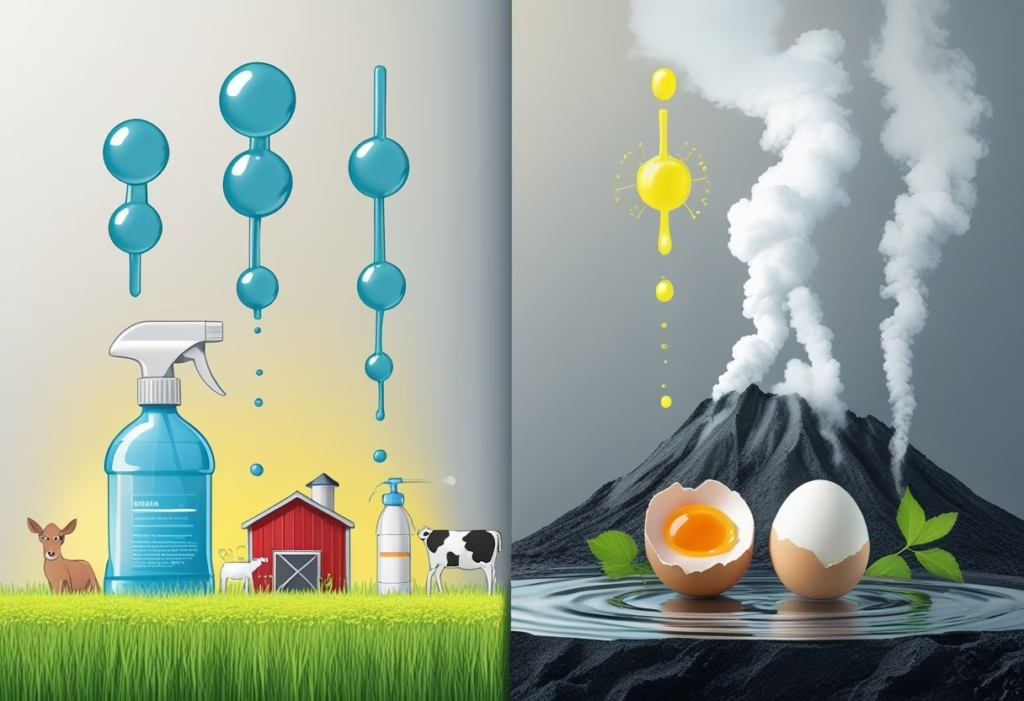

Specific bacterial genera produce distinct odorants. Trimethylamine results when gut bacteria metabolize choline and carnitine from red meat, eggs, and fish. This compound smells like rotting fish and intensifies when your liver cannot efficiently convert it to odorless trimethylamine oxide.

Bacterial fermentation of amino acids also produces short-chain fatty acids, ammonia, and aromatic compounds. Putrescine and cadaverine form from incomplete protein breakdown and smell like decaying meat. The balance of beneficial versus harmful bacteria determines how much of these metabolites accumulate.

People often make the mistake of only focusing on external hygiene while ignoring their gut microbiota composition. High-protein diets without adequate fiber can worsen bacterial production of ammonia and sulfur compounds.

Circulation of Volatile Compounds

Bacterial metabolites produced in your gut lumen cross into your bloodstream through the intestinal barrier. Your liver processes most of these compounds, but when production exceeds your liver’s capacity or gut permeability increases, more odorants enter circulation.

Volatile compounds travel through your blood to various excretion points. Your lungs release them in your breath, your kidneys filter them into urine, and your sweat glands expel them through your skin. This explains why malodor often affects multiple body sites simultaneously.

Leaky gut syndrome significantly worsens this process. When your intestinal barrier becomes compromised through inflammation, stress, or poor diet, larger quantities of bacterial metabolites penetrate into circulation. Your body struggles to eliminate the excess load of volatile organic compounds.

Kidney and liver function directly affect odor intensity. Reduced kidney filtration allows uremic compounds to accumulate, causing an ammonia-like breath and body smell. Impaired liver metabolism prevents conversion of trimethylamine to its odorless form.

The Gut-Skin Axis and Odor Expression

Your gut microbiome influences skin bacteria composition through immune signaling and metabolite circulation. When gut dysbiosis occurs, altered metabolic byproducts reach your skin and change the local bacterial environment. Skin bacteria then convert sweat compounds into additional odorous molecules.

The interaction between circulating gut metabolites and skin flora amplifies body odor. For example, when gut bacteria produce excess phenolic compounds, these reach your skin where Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus species convert them into more volatile odorants.

What makes symptoms worse: consuming processed foods, antibiotics that disrupt gut balance, chronic constipation that increases bacterial fermentation time, and stress that compromises gut barrier function. Rapid transit through a healthy gut reduces bacterial metabolite production.

You should consult a doctor if body odor persists despite good hygiene, suddenly changes character, or accompanies other symptoms like digestive issues or fatigue. This may indicate underlying conditions affecting gut or metabolic function.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Microbial and Chemical Contributors to Body Odor

Specific bacterial species on your skin and in your mouth transform odorless compounds from sweat and saliva into volatile chemicals that create distinct smells. The types of bacteria present and the chemical compounds they produce determine whether your body odor smells like rotten eggs, fish, or sweaty feet.

Key Odor-Producing Bacteria

Corynebacterium and Staphylococcus are the primary bacteria responsible for armpit odor. These bacteria break down lipids and amino acids in apocrine sweat into smelly compounds. Corynebacterium species produce particularly pungent odors because they generate 3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid, which creates that characteristic sharp, sweaty smell.

Staphylococcus bacteria convert branched-chain amino acids into isovaleric acid, which smells like cheese or sweaty feet. Some Staphylococcus strains also produce 3-hydroxy-3-methylhexanoic acid, contributing to rancid odors.

In your mouth, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium produce volatile sulfur compounds that cause bad breath. Treponema denticola works alongside these bacteria to break down proteins into sulfur-containing amino acids. Veillonella species metabolize lactate and produce short-chain fatty acids that add to oral malodor.

The specific bacterial composition varies between individuals, which explains why two people eating the same foods can smell completely different.

Role of Volatile Sulfur Compounds

Volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) include hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol, and dimethyl sulfide. Hydrogen sulfide creates the rotten egg smell you notice in bad breath and flatulence. Methanethiol produces a putrid, barnyard-like odor.

These compounds form when bacteria break down sulfur-containing amino acids like cysteine and methionine from proteins in food or saliva. The process happens most actively in areas with low oxygen, such as deep in tongue crevices or between teeth.

VSCs become more concentrated when you have poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease, or dry mouth. Saliva normally helps wash away bacteria and their metabolites, so reduced saliva flow allows VSC levels to increase dramatically. Eating foods high in sulfur compounds like garlic, onions, or cruciferous vegetables provides more substrate for bacteria to convert into VSCs.

If brushing, flossing, and tongue scraping don’t reduce sulfur-smell breath after two weeks, see a dentist to check for gum disease or other oral health issues.

Trimethylamine and Other Notable Odorants

Trimethylamine (TMA) creates a distinctive fishy smell in breath, sweat, and urine. Gut bacteria produce TMA when they metabolize choline, carnitine, and lecithin from foods like eggs, fish, and red meat. Your liver normally converts TMA into odorless trimethylamine oxide, but some people have reduced enzyme function that allows TMA to accumulate.

When TMA enters your bloodstream from the gut, it gets released through sweat glands and breath, creating persistent fishy body odor even with good hygiene. This condition, called trimethylaminuria, worsens with high-protein diets or gut bacterial overgrowth.

Indole and skatole smell like fecal matter and result from bacterial breakdown of tryptophan. Putrescine and cadaverine create rotten meat odors from amino acid decarboxylation. Ammonia produces a urine-like smell when protein waste accumulates.

Acetone causes fruity breath in uncontrolled diabetes but isn’t bacterial in origin. Most bacterial odorants worsen with constipation, antibiotic use, or high-protein diets because these factors alter gut bacterial populations and increase substrate availability for odor production.

Body Sites, Sweat Glands, and Odor Manifestations

Different types of sweat glands produce distinct secretions that bacteria metabolize into odorous compounds, while specific body sites harbor unique bacterial communities that generate characteristic smells ranging from armpit odor to breath malodor caused by oral bacteria.

Eccrine vs. Apocrine Glands

Your body contains two main sweat gland types that function very differently. Eccrine glands cover most of your skin surface and produce watery sweat composed mainly of salt and water. This sweat is nearly odorless on its own.

Apocrine glands become active during puberty and concentrate in hair-bearing areas like your armpits, groin, and scalp. These glands secrete a thicker, oily fluid containing proteins, lipids, and steroids that bacteria readily break down into smelly compounds.

Common mistake: Believing sweat itself causes odor. The secretions are initially odorless, but skin bacteria metabolize the compounds into volatile molecules you can smell.

Apocrine sweat provides significantly more fuel for bacterial metabolism than eccrine sweat. This explains why your armpits smell stronger than your forearms even when both areas sweat heavily.

Skin Microbiota and Site-Specific Odor

Bacteria on your skin metabolize sweat compounds to produce the specific odors you experience at different body sites. The bacterial species present determine which odorous molecules form.

Your armpit microbiota typically breaks down apocrine secretions into several distinct compounds:

- Short-chain fatty acids (butyric, isovaleric acid): produce cheesy, sweaty feet odors

- (E)-3-methyl-2-hexenoic acid: creates pungent body odor

- 3-methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol: generates onion-like smells

Different body regions harbor distinct bacterial populations. Your feet accumulate bacteria that thrive in warm, moist environments and produce isovaleric acid, explaining the characteristic foot odor. Your groin area contains bacteria that metabolize steroids and proteins into ammonia-related compounds.

What makes it worse: Occlusive clothing traps moisture and heat, allowing bacteria to multiply rapidly. Shaving can temporarily increase odor by creating micro-abrasions where bacteria colonize more easily.

Beyond the Skin: Breath and Other Odor Sites

Approximately 20-50% of adults experience halitosis, with 80-90% of cases originating from oral sources. Tongue coating and dental plaque harbor bacteria that produce volatile sulfur compounds including hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg smell) and methanethiol (putrid odor).

Intra-oral halitosis develops when oral bacteria like Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia break down proteins in saliva and food debris. These bacteria accumulate on your tongue’s posterior surface and in periodontal pockets.

Extra-oral halitosis occurs when gut-derived bacterial metabolites enter your bloodstream and exit through your lungs. Your gut bacteria produce trimethylamine (fishy smell), ammonia, and other volatile compounds that can manifest in breath odor when liver or kidney function is compromised.

When to see a doctor: Persistent breath odor despite good oral hygiene may indicate diabetes, liver disease, or kidney problems. Sudden changes in body odor warrant medical evaluation.

Medical disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes and does not replace professional medical advice.

Diet, Lifestyle, and Conditions Influencing Odor

Certain foods directly feed odor-producing bacteria in your gut, while digestive efficiency and basic hygiene practices determine how effectively your body eliminates these compounds before they reach your skin and breath.

Dietary Triggers and Microbial Metabolism

When you eat foods high in sulfur compounds like garlic, onions, or cruciferous vegetables, gut bacteria break them down into volatile sulfur compounds that enter your bloodstream and exit through sweat and breath. Meat-rich diets influence gut bacteria composition, creating more volatile compounds that intensify body odor.

Red meat requires longer digestion time, allowing bacteria to produce more putrescine and cadaverine—compounds that smell like rotten meat. This happens because protein fermentation in your colon generates these odor-causing bacteria byproducts.

Foods that typically worsen odor:

- Red meat and processed meats

- Garlic, onions, and leeks

- Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cabbage)

- Spicy foods with cumin or curry

- Alcohol

Foods that may reduce odor:

- Fermented foods (yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut)

- Leafy greens and parsley

- Citrus fruits

- Fiber-rich foods that speed transit time

Probiotic foods and fiber-rich options balance gut bacteria and reduce odor-causing byproducts. The mistake many people make is eliminating all sulfur-containing vegetables when these foods feed beneficial bacteria that crowd out more problematic strains.

Role of Digestion and Intestinal Transit Time

Your intestinal transit time—how quickly food moves through your digestive system—directly affects odor intensity. Slower transit allows bacteria more time to ferment food and produce odorous metabolites.

When gut function is compromised, intestinal transit time and gut-blood barrier permeability affect how bacterial metabolites enter your bloodstream. A “leaky gut” lets more odorous compounds pass through intestinal walls into circulation, where they’re eventually released through sweat glands and lungs.

Constipation creates the worst scenario: waste sits in your colon for extended periods while bacteria generate hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol, and ammonia. These compounds accumulate and eventually permeate through your gut lining.

Your liver normally metabolizes gut-derived bacterial metabolites—for example, converting trimethylamine (which smells like rotten fish) into odorless trimethylamine oxide. When digestive health is poor or liver function is reduced, these conversions happen less efficiently.

What usually helps: Consuming 25-35 grams of fiber daily, staying active to stimulate bowel movements, and eating at regular times. What rarely helps: Taking fiber supplements without adequate water, which can worsen constipation.

Impact of Hydration and Personal Hygiene

Dehydration concentrates odorous compounds in your sweat and urine, making them more noticeable. When you’re adequately hydrated, your kidneys flush out bacterial metabolites more efficiently before they accumulate.

Staying hydrated is essential for odor control alongside diet and personal hygiene. Your kidneys eliminate both bacterial metabolites and their precursor substrates from blood—but this only works effectively with sufficient fluid intake.

Personal hygiene matters because sweat itself doesn’t smell until skin bacteria break it down. Apocrine sweat glands in your armpits and groin produce protein-rich sweat that bacteria metabolize into odorous compounds within hours.

Showering removes accumulated bacteria and the secretions they feed on. Using antibacterial soap can help, but overuse disrupts your skin microbiome and sometimes worsens odor by eliminating protective bacteria that compete with odor-causing strains.

Common mistakes: Wearing synthetic fabrics that trap moisture and heat, creating ideal conditions for bacterial growth. Breathable fabrics like cotton allow sweat evaporation and reduce bacterial proliferation.

When to see a doctor: If you notice sudden changes in body odor accompanied by fatigue, excessive thirst, or dark urine—these may indicate diabetes or kidney problems requiring medical evaluation.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of any medical conditions.

Disorders Associated With Gut-Related Body Odor

Several specific medical conditions create body odor through gut-related mechanisms, ranging from genetic enzyme deficiencies to organ dysfunction. These disorders share a common pathway where compounds produced or processed in the gut accumulate and emit odor through breath, sweat, or urine.

Trimethylaminuria (Fish Odor Syndrome)

Trimethylaminuria occurs when your body cannot properly break down trimethylamine, a compound that gut bacteria produce when they digest foods containing choline, carnitine, and lecithin. This happens due to FMO3 deficiency, where the liver enzyme flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 fails to convert trimethylamine into trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), which has no odor.

The unmetabolized trimethylamine accumulates in your body and escapes through sweat, breath, and urine, creating a distinctive fishy smell. The odor intensity varies based on what you eat and hormonal fluctuations.

Foods that make TMAU worse include:

- Eggs and egg-rich dishes

- Saltwater fish and seafood

- Organ meats and red meat

- Legumes and soybeans

- Cruciferous vegetables like broccoli and Brussels sprouts

You should see a doctor if you notice persistent fishy odor that doesn’t improve with regular hygiene. Testing involves measuring trimethylamine levels in urine after a choline challenge test. While no cure exists, controlling your diet by limiting choline-rich foods usually helps manage symptoms, whereas using stronger soaps or deodorants rarely helps since the odor comes from inside your body.

Metabolic and Organ Disorders

Several congenital metabolic diseases create distinctive odors when your body cannot process specific amino acids or compounds. Phenylketonuria produces a musty or mousy smell in urine and on infant skin because phenylalanine accumulates and converts to phenylacetate. Maple syrup urine disease creates a sweet, burnt sugar smell when branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) build up in urine and ear wax.

Kidney disease and liver failure both cause breath odor through different mechanisms. When your kidneys fail, they cannot properly excrete waste products, leading to uremic fetor—an ammonia-like or fishy breath smell from accumulated urea and trimethylamine. Liver failure produces fetor hepaticus, a musty or sweet breath odor, because your damaged liver cannot metabolize gut-derived bacterial compounds like ammonia and methionine metabolites.

These conditions worsen when protein intake increases because more nitrogen waste enters circulation. You need immediate medical attention if you develop sudden breath changes with confusion, fatigue, or swelling, as these signal organ failure requiring urgent treatment.

Dysbiosis and Gut Imbalance

Gut dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in your intestinal bacterial composition, which increases production of odorous compounds. When harmful bacteria overgrow or beneficial bacteria decline, your gut produces excessive amounts of volatile sulfur compounds, ammonia, and short-chain fatty acids that enter your bloodstream and emit through your breath and skin.

A common mistake is assuming better hygiene solves dysbiosis-related odor. The problem originates internally, so external cleaning provides only temporary relief.

Conditions that promote gut dysbiosis include:

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

- Inflammatory bowel diseases

- Prolonged antibiotic use

- High-sugar, low-fiber diets

- Chronic stress

Bacterial vaginosis represents localized dysbiosis that causes fishy-smelling vaginal discharge through similar bacterial imbalances. Studies show that changes in gut microbiome composition directly correlate with body malodor severity, particularly when bacteria that normally live on skin increase in the intestines.

Probiotic supplementation and dietary changes that support beneficial bacteria usually help restore balance, while masking products rarely address the underlying cause. See a doctor if you experience persistent unusual body odor alongside digestive symptoms like bloating, irregular bowel movements, or abdominal discomfort.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment of any medical condition.

Strategies to Manage Gut-Related Body Odor

Managing body odor that originates from gut bacteria requires addressing internal microbial balance alongside external hygiene practices. The most effective approaches combine dietary modifications, targeted bacterial management, and knowing when medical intervention becomes necessary.

Probiotics and Prebiotics for Odor Control

Probiotics work by introducing beneficial bacteria that can reduce the production of odorous compounds in your gut. When you take a probiotic supplement, the new bacterial strains compete with odor-producing bacteria for resources and space in your digestive system.

However, reducing the dosage when starting probiotics allows your gut microbiome to adjust gradually, which lessens the immediate production of odor-causing compounds. Some people experience temporarily worse body odor when first taking probiotics because die-off of existing bacteria releases additional metabolites into your bloodstream.

Not all probiotic strains address body odor equally. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species show the most promise because they produce lactic acid, which lowers gut pH and inhibits putrefactive bacteria that generate trimethylamine and volatile sulfur compounds.

Prebiotics like inulin and fructooligosaccharides feed beneficial bacteria already in your gut. Taking prebiotics without probiotics can be more effective if you already have good bacterial diversity but need to support their growth. The combination rarely helps more than taking one or the other unless you have severe dysbiosis.

A common mistake is expecting immediate results. Meaningful shifts in gut bacteria take 4-8 weeks of consistent supplementation.

Physical and Topical Approaches

Physical elimination of bacteria from skin surfaces remains essential because even when gut bacteria produce fewer odorous compounds, skin bacteria still metabolize sweat into smelly substances. Regular bathing removes both bacteria and accumulated odorants, but over-washing strips protective skin oils and can worsen odor by disrupting your skin’s natural bacterial balance.

Antiperspirant works differently than deodorant by blocking sweat glands, which reduces the moisture that skin bacteria need to thrive. This proves more effective for underarm odor than deodorant alone because it addresses the root cause rather than masking smell.

Antibacterial soaps seem logical but usually make things worse long-term. They kill beneficial skin bacteria that compete with odor-producing species, allowing problem bacteria to repopulate more aggressively. Gentle cleansers maintain a healthier skin microbiome.

Wearing breathable natural fabrics like cotton allows sweat to evaporate rather than creating a warm, moist environment where bacteria multiply rapidly. Synthetic materials trap moisture and body heat, which accelerates bacterial growth and odor production.

Medical Evaluation and When to Seek Help

You should seek medical evaluation if body odor persists despite improved hygiene and dietary changes, particularly if the smell is unusual or accompanied by other symptoms. Persistent or unusual body odor can indicate underlying health issues including liver dysfunction, kidney disease, or metabolic disorders.

Sudden changes in body odor warrant attention. A fishy smell might indicate trimethylaminuria, while a fruity or acetone-like breath odor could signal diabetic ketoacidosis, which requires immediate medical attention.

Your doctor can order tests to measure specific metabolites in blood and urine that reveal whether your liver is properly processing gut-derived compounds like trimethylamine. Elevated levels indicate your body cannot neutralize these odorants effectively.

Some people develop severe psychological distress from perceived body odor that others cannot detect. This condition, called olfactory reference syndrome, requires mental health support rather than physical treatments for odor.

Medical Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider before starting any supplement regimen or if you experience persistent body odor concerns.